Perjanjian Waitangi

Tolong bantu menterjemahkan sebahagian rencana ini. Rencana ini memerlukan kemaskini dalam Bahasa Melayu piawai Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. Sila membantu, bahan-bahan boleh didapati di Treaty of Waitangi (Inggeris). Jika anda ingin menilai rencana ini, anda mungkin mahu menyemak di terjemahan Google. Walau bagaimanapun, jangan menambah terjemahan automatik kepada rencana, kerana ini biasanya mempunyai kualiti yang sangat teruk. Sumber-sumber bantuan: Pusat Rujukan Persuratan Melayu. |

| Perjanjian Waitangi Treaty of Waitangi Te Tiriti o Waitangi | |

|---|---|

Treaty to establish a British Governor of New Zealand, consider Māori ownership of their lands and other properties, and gave Māori the rights of British subjects. | |

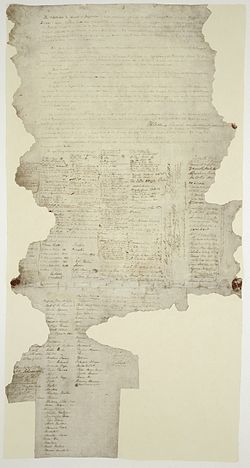

Salah satu salinan Perjanjian Waitangi yang masih wujud | |

| Dirangka | 4—5 Februari 1840 oleh William Hobson dengan bantuan setiausahanya James Freeman dan Residen British James Busby |

| Ditandatangani | 6 Februari 1840 di Waitangi, Bay of Islands, New Zealand serta lokasi-lokasi lain. Kini disimpan di Arkib Negara New Zealand, Wellington. |

| Penandatangan | Wakil-wakil diraja British Crown, ketua-ketua puak-puak orang Māori daripada bahagian utara Pulau Utara, serta 500 orang penandatangan yang lain. |

| Bahasa | Inggeris, Māori |

Laman sesawang | Treaty of Waitangi |

| sunting | |

Perjanjian Waitangi (bahasa Maori: Tiriti o Waitangi) adalah perjanjian yang pertama kalinya ditandatangani pada 6 Februari 1840 oleh wakil-wakil Mahkota British dan pelbagai ketua-ketua Maori dari Pulau Utara New Zealand. Tindakan tersebut membawa kepada pengisytiharan kedaulatan Britain ke atas New Zealand oleh Leftenan Gabenor William Hobson pada Mei 1840.

Perjanjian ini menetapkan Gabenor British bagi New Zealand, mengiktiraf pemilikan tanah dan harta lain kaum Māori serta memberi kaum Māori hak warganegara British. Versi bahasa Inggeris dan bahasa Maori mengenai Perjanjian tersebut mempunyai perbezaan yang ketara, dengan itu tidak terdapat persetujuan dengan tepat apa mengenai apa yang telah dipersetujui. Dari sudut pandangan British, Perjanjian ini menyerahkan Britain kuasa kedaulatan ke atas New Zealand, dan memberikan Gabenor hak untuk memerintah negara ini. Maori percaya bahawa mereka menyerahkan kepada Mahkota hak urus tadbir sebagai balasan untuk perlindungan, tanpa memberi menyerahkan hak mereka untuk mengurus hal ehwal mereka sendiri.[1] Selepas tandatangan awal di Waitangi, salinan-salinan Perjanjian ini telah dibawa sekitar New Zealand dan ramai ketua-ketua puak yang lain turut menandatanganinya pada beberapa bulan berikut. Secara keseluruhannya, terdapat sembilan salinan Perjanjian Waitangi termasuk yang asal yang ditandatangani pada 6 Februari 1840.[2] Kira-kira 500 ketua kampung, termasuk sekurang-kurangnya 13 orang perempuan, menandatangani Perjanjian Waitangi.[3]

Sehingga tahun 1970-an, perjanjian ini secara amnya tidak dipedulikan kedua-dua bahagian kehakiman dan Parlimen New Zealand, namun ia mendapat tanggapan dalam sejarah am New Zealand sebagai suatu tindakan yang ikhlas dari pihak kerajaan British.[4] Selewat tahun 1860-an, masyarakat Māori telah merujuk kepada Perjanjian ini untuk mendapatkan hak dan pampasan mereka berkaitan kehilangan milik tanah mereka serta pelayanan tidak setara daripada kerajaan, dengan sedikit sahaja usaha yang berjaya. Daripada lewat 1960-an, orang Māori mula menumpukan perhatian kepada kes-kes pelanggaran Perjanjian ini, dengan perbincangan yang berlanjutan turut menekankan masalah berkaitan terjemahan perjanjian ini.[5] Pada 1975, Tribunal Waitangi diasaskan sebagai sebuah suruhanjaya tetap penyiasatan yang ditugaskan menyelidiki sebarang pelanggaran kepada perjanjian ini yang dilakukan Kerajaan New Zealand mahupun ejen-ejennya serta mencadangkan cara tebus rugi yang bersesuaian.

Perjanjian ini kini dianggap sebagai dokumen pengasasan negara New Zealand. Meskipun begitu, kandungan Perjanjian ini seringkali menjadi suatu perkara yang hangat dihujahkan. Kebanyakan daripada orang Māori merasakan pihak Kerajaan tidak memenuhi kewajibannya dalam perjanjian ini, dan mereka telah mengemukakan bukti-bukti perkara sebegini di hadapan perbicaraan Tribunal. Terdapat segelintir warga New Zealand bukan Māori yang menyatakan bahawa orang Māori barangkali menyalahgunakan Perjanjian ini untuk meraih "keistimewaan tertentu".[6]Ralat petik: Tag <ref> tidak sah; nama-nama tidak sah, misalnya terlalu banyak Dalam kebanyakan kes, pihak Kerajaan tidak wajib bertindak atas cadangan Tribunal ini. Walau bagaimanapun, pihak tersebut turut mengakui bahawa ia telah melanggar Perjanjian itu serta prinsip-prinsipnya dalam banyak kes. Penyelesaian yang dituntut daripada Perjanjian ini dikira sebanyak berjuta-juta dolar dalam bentuk wang dan aset serta juga permohonan minta maaf bagi pihak Kerajaan.

Tarikh penandatanganan perjanjian ini telah disambut sebagai satu cuti kebangsaan melalui pemaktuban Akta Hari New Zealand 1973 (New Zealand Day Act 1973) sebagai Hari Waitangi yang bermula sejak tahun 1974.

Latar belakang[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada awal abad ke-19, penduduk Māori begitu terganggu dengan perangai dan niat para peniaga, pemburu-pemburu paus dan anjing laut yang tiba ke negara ini, terutamanya di Bay of Islands. Teknologi senapang lantak yang diperkenalkan telah mengurangkan pendudukan orang Māori secara drastik nya melalui beberapa perang yang berlaku pada awal abad ke-19.[7] Pada tahun 1831, tiga belas rangatira daripada hujung utara negara bertemu di Kerikeri untuk mengutus surat kepada Raja William IV memohon perlindungan ke atas tanah mereka. Secara telitinya, ketua-ketua ini meminta pertolongan Perancis, "puak Marion", di mana ia merupakan surat pertama yang ditulis orang Māori meminta campur tangan British.[8] Kerajaan British bertindak menghantar James Busby pada 1832 menjadi Residen New Zealand. Pada 1834, Busby membuat sebuah draf dokumen yang dikenali sebagai Perisytiharan Kemerdekaan New Zealand di mana ia ditandatangani beliau dan 35 orang ketua puak Māori utara di Waitangi pada 28 Oktober 1835, menetapkan ketua-ketua tersebut sebagai wakil sebuah proto-negara di bawah nama Puak-puak Bersatu New Zealand (United Tribes of New Zealand). Dokumen ini tidak diterima dengan baiknya oleh Pejabat Jajahan di Britain, dan suatu persepakatan dibuat untuk membentuk polisi baru yang perlu untuk New Zealand.[9]

Pada May hingga Julai 1836, seorang pegawai Tentera Laut Diraja British bernama Kapten William Hobson, diperintahkan Richard Bourke untuk melawat New Zealand melakukan penyiasatan terhadap dakwaan huru-hara di jajahan tersebut. Hobson mencadangkan dalam laporannya bahawa New Zealand diletakkan bawah kedaulatan British dalam skala kecil sepertimana peranan Syarikat Teluk Hudson di Kanada.[10] Laporan Hobson itu diserahkan kepada Pejabat Jajahan dan dari April hingga Mei 1837, Dewan Pertuanan mengadakan sebuah suruhanjaya rahsia terhadap keadaan pulau-pulau New Zealand (State of the Islands of New Zealand). New Zealand Association (kemudiannya Syarikat New Zealand), para mubaligh serta Tentera Laut Diraja menghantar surat kepada suruhanjaya tersebut. Suruhanjaya ini mencadangkan sebuah perjanjian yang bakal dimeterai dengan orang Māori.[10]

Historian Claudia Orange claims that the Colonial Office had initially planned a "Māori New Zealand" in which European settlers would be accommodated, but by 1839 had shifted to "a settler New Zealand in which a place had to be kept for Māori" due to pressure from the New Zealand Company[7] which hurriedly dispatched the Tory to New Zealand on 12 May 1839[11] (arriving in Port Nicholson (Wellington) on 20 September 1839 to purchase land) and plans by French Captain Jean François L'Anglois for a French colony in Akaroa.[12]

On 15 June 1839 new Letters Patent were issued to expand the territory of New South Wales to include the entire territory of New Zealand, from latitude 34° South to 47° 10’ South, and from longitude 166° 5’ East to 179° East.[13] Governor of New South Wales George Gipps was appointed Governor over New Zealand. This was the first clear expression of British intent to annexe New Zealand.

Captain William Hobson was called to the Colonial Office on the evening of 14 August 1839 and given instructions to take the constitutional steps needed to establish a British colony. Historian Paul Moon believes the instructions were written by Sir James Stephen, then head of the Colonial Office.[14] However, T. Lindsay Buick in his landmark 1914 book 'The Treaty of Waitangi:or how New Zealand became a British Colony', clearly reproduces written instructions drafted by Edward Cardwell of the Colonial Office (Cardwell later became Viscount Cardwell and was most noted for his reforms of the British Army after the disaster of the Crimean War). Hobson was appointed Consul to New Zealand. He was instructed to negotiate a voluntary transfer of sovereignty from Māori to the British Crown as the House of Lords select committee had recommended in 1837.[15] Hobson left London on 15 August 1839 and was sworn in as Lieutenant-Governor in Sydney on 14 January, finally arriving in the Bay of Islands on 29 January 1840. Meanwhile a second ship, the Cuba, had arrived in Port Nicholson on 3 January with a survey party to prepare for settlement.[16] The first ship carrying immigrants arrived on 22 January – the Aurora.[17]

On 30 January 1840 Hobson attended the Christ Church at Kororareka (Russell) where he publicly read a number of proclamations. The first was the Letters Patent 1839, in relation to the extension of the boundaries of New South Wales to include the islands of New Zealand. The second was in relation to Hobson's own appointment as Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand. The third was in relation to land transactions (notably on the issue of pre-emption).[18]

Without a draft document prepared by lawyers or Colonial Office officials, Hobson was forced to write his own treaty with the help of his secretary, James Freeman, and British Resident James Busby, neither of whom was a lawyer. Historian Paul Moon believes certain articles of the Treaty resemble the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), the British Sherbo Agreement (1825) and the Treaty between Britain and Soombia Soosoos (1826).[19] The entire treaty was prepared in four days.[7] Realising that a treaty in English could be neither understood, debated or agreed to by Māori, Hobson instructed missionary Henry Williams and his son Edward to translate the document into Māori and this was done overnight on 4 February.

Perbahasan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada 5 Februari salinan perjanjian dalam kedua-dua bahasa telah diletakkan sebelum perhimpunan ketua-ketua utara di dalam marquee yang besar di halaman di depan rumah Busby di Waitangi. Hobson membaca perjanjian itu dengan lantang dalam bahasa Inggeris dan Williams membaca versi Māorinya. Ketua ketua Māori ( rangatira ) kemudian membahaskan perjanjian itu selama lima jam, sebahagian besarnya telah dicatat dan diterjemahkan oleh pencetak stesen misionaris Paihia, William Colenso.[20] Rewa, seorang ketua Katolik, yang telah dipengaruhi oleh Uskup Katolik Perancis Pompelier, berkata, "Orang Māori tidak menginginkan seorang gubernur! Kami bukan orang Eropah, memang benar kami telah menjual sebagian tanah kita, tetapi negara ini masih kita, ketua-ketua kita yang memerintah tanah nenek moyang kita ", Moka 'Kainga-mataa' berpendapat bahawa semua tanah yang tidak dibeli oleh orang Eropah tidak boleh dikembalikan.[21] Whai bertanya: "Semalam saya dikutuk oleh seorang lelaki kulit putih, apakah itu akan menjadi perkara yang akan berlaku?". Ketua Protestan seperti Hone Heke, Pumuka, Te Wharerahi, Tamati Waka Nene dan abangnya Eruera Maihi Patuone menerima Gubernur.[21] Hone Heke berkata, "Gabenor, anda harus tinggal bersama kami dan menjadi seperti seorang bapa, jika anda pergi, maka penjual Perancis atau rum akan membawa kami kepada orang Māori, bagaimana dengan anda, sebahagian daripada anda memberitahu Hobson untuk pergi. akan menyelesaikan kesukaran kami, kami telah menjual banyak tanah di sini di utara Kami tidak mempunyai cara untuk mengawal orang Eropah yang telah menetap di atasnya Saya kagum mendengar anda memberitahu dia untuk pergi! peniaga-peniaga dan peniaga-peniaga untuk pergi bertahun-tahun yang lalu? Terdapat terlalu ramai orang Eropah di sini sekarang dan ada anak-anak yang akan menyatukan kaum kita ".[21]. Uskup Katolik Perancis Pompelier, yang telah menasihatkan banyak Maori Katolik di utara mengenai perjanjian itu, menggesa mereka supaya sangat waspada terhadap perjanjian itu dan tidak menandatangani apa-apa. Beliau meninggalkan selepas perbincangan awal dan tidak hadir apabila ketua-ketua menandatangani.<P.Lowe.The French and The Maori.Heritage.1990.>

Selepas itu, ketua-ketua kemudian berpindah ke sebuah sungai yang rata di bawah rumah Busby dan padang dan perbincangan terus larut malam.

Penandatanganan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Meskipun Hobson merancang penandatanganan tersebut untuk berlaku pada 7 Februari, sebanyak 45 orang ketua puak telah tiba seawal pagi hari sebelumnya untuk menandatangan perjanjian tesebut, lalu Hobson tergesa-gesa membuat persediaan atas rancangan ini.[20]

Hobson mengetuai pihakpenandatangan British. Dari pihak Māori pula, Hone Heke merupakan ketua pertama yang memnandatangani perjanjian ini. Hobson berkata "He iwi tahi tātou", ("Kita kini merupakan satu masyarakat yang bersatu") sambil ketua-ketua Māori yang lain meneruskan penandatanganan perjanjian ini.[21]

Keseluruhannya sebanyak 150 orang ketua puak utara kebanyakannya daripada Nga Puhi menandatangani Perjanjian ini pada hari tersebut.[22] 44 ketua puak Waikato-Tainui turut menandatangani Perjanjian ini.[23]

Sebagai pengukuhan kuasa perjanjian tersebut, sebanyak lapan salinan lagi telah dibuat dan dihantar ke serata negara untuk mengumpul lebih tanda tangan:

- salinan Manukau-Kawhia,

- salinan Waikato-Manukau,

- salinan Tauranga,

- salinan Bay of Plenty,

- salinan Herald-Bunbury,

- salinan Henry Williams,

- salinan East Coast dan

- salinan bercetak.

About 50 meetings were held from February to September 1840 to discuss and sign the copies, and a further 500 signatures were added to the treaty. A number of chiefs and some tribal groups refused to sign, including Pōtatau Te Wherowhero (Waikato iwi), Tuhoe, Te Arawa and Ngāti Tuwharetoa and possibly Moka 'Kainga-mataa'. Some were not given the opportunity to sign.[21] A number of non-signatory Waikato and Central North Island chiefs would later form a kind of confederacy with an elected monarch called the Kingitanga. (The Kingitanga Movement would later form a primary anti-government force in the New Zealand Land Wars.)

Pada 21 Mei 1840, Leftenan Gabenor Hobson mengisytiharkan kedaulatan Britain ke atas seluruh negara itu (Pulau Utara melalui Perjanjian ini dan Pulau Selatan melalui penemuan) dan New Zealand dipisahkan sebagai jajahan yang berasingan daripada New South Wales pada 16 November 1840.

Hari ulang tahun penandatanganan perjanjian ini diperibgati sebagai cuti umum di New Zealand bernama Hari Waitangi pada 6 Februari. Sambutan Waitangi Day pertama dilakukan pada 1947 (meskipun ada terdapat juga majlis peringatan sebelum ini) dan hari tersebut tidak dijadikan cuti am sehingga 1974. The commemoration has often been the focus of protest by Māori and frequently attracts controversy. The anniversary is officially commemorated at the Treaty house at Waitangi, where the Treaty was first signed.

Salinan yang masih ada[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada tahun 1841, Perjanjian ini sempat melarikan diri dengan kemusnahan apabila pejabat kerajaan di Auckland dimusnahkan oleh api. Apabila ibukota dipindahkan dari Auckland ke Wellington pada tahun 1865, dokumen Perjanjian ditandatangani bersama-sama dan disimpan di tempat selamat di Pejabat Setiausaha Kolonial (New Zealand) | . Dokumen-dokumen tersebut tidak disentuh sehingga mereka dipindahkan ke Wellington pada tahun 1865, apabila terdapat senarai penandatangan.

Pada tahun 1877, draf kasar bahasa Inggeris diterbitkan bersama-sama dengan fotolitografi faksimili Perjanjian, dan asal-usul itu dikembalikan ke simpanan. Pada tahun 1908, Dr Hocken mendapati Perjanjian di dalam keadaan miskin, sebahagiannya dimakan oleh tikus. Dokumen itu telah dipulihkan oleh Dominion Museum pada tahun 1913.

Pada bulan Februari 1940, Perjanjian ini dibawa ke Waitangi untuk dipamerkan di rumah Perjanjian semasa perayaan Centennial Centennial Centennial - ini mungkin kali pertama Perjanjian telah dipaparkan di muka umum sejak ditandatangani.

Selepas meletusnya peperangan dengan Jepun, Perjanjian ini telah ditempatkan dengan dokumen negara lain di luar bagasi bagasi dan didepositkan untuk mendapatkan jagaan selamat dengan Pemegang Amanah Awam di Palmerston North oleh anggota MP yang tidak memberitahu kakitangan mengenai perkara itu. Walau bagaimanapun, kerana kes itu terlalu besar untuk dimuatkan dengan selamat, Perjanjian ini menghabiskan perang di sebelah koridor belakang di pejabat Amanah Awam.

Pada tahun 1956, [[Jabatan Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri (Jabatan Hal Ehwal Dalam Negeri)] meletakkan Perjanjian ke dalam penjagaan Perpustakaan Alexander Turnbull dan akhirnya dipaparkan pada tahun 1961. Langkah-langkah pemeliharaan selanjutnya diambil di 1966, dengan penambahbaikan kepada keadaan paparan. Dari tahun 1977 hingga 1980, perpustakaan itu telah memulihkan semula dokumen-dokumen tersebut sebelum Perjanjian tersebut disimpan di Bank Rizab.

Dalam menjangkakan keputusan untuk memperlihatkan perjanjian itu pada tahun 1990 (seperempat tahun penandatanganan), dokumentasi penuh dan fotografi pembiakan telah dijalankan. Beberapa tahun perancangan memuncak dengan pembukaan Bilik Perlembagaan pada masa itu Arkib Negara oleh [[Mike Moore (ahli politik New Zealand) | Mike Moore], Perdana Menteri New Zealand, pada November 1990. Dokumen-dokumen itu kini pada paparan tetap di Bilik Perlembagaan di ibu pejabat Archives New Zealand di Wellington.

Makna dan pentakrifan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Perjanjian tersebut ringkas dengan sebuah mukadimah serta tiga perkara. Mukadimah perjanjian tersebut menyatakan bahawa Ratu Victoria "berhasrat mendirikan sebuah Kerajaan Sivil yang teguh", dan mengundang ketua-ketua puak Māori menyetujui perkara-perkara berikutnya. Perkara pertama dokumen perjanjian ini versi bahasa Inggeris mengurniakan kedaulatan "Ratu England" (United Kingdom sebenarnya) ke atas New Zealand. Perkara kedua menjamin ketua-ketua Māori "pemilikan Tanah, Estet, Hutan, Perairan dan milik lain mereka eksklusif dan tidak terganggu" secara sepenuhnya. Ia juga menetapkan bahawa orang Māori akan menjual tanah mereka kepada Mahkota British sahaja. Perkara ketiga menjamin hak sama yang dipegang warga British yang lain ke atas semua orang Māori.

The English and Māori versions differ. This has made it difficult to interpret the Treaty and continues to undermine its effect. The most critical difference revolves around the interpretation of three Māori words: kāwanatanga (governorship), which is ceded to the Queen in the first article; rangatiratanga (chieftainship) not mana (which was stated in the Declaration of Independence just five years before the Treaty was signed), which is retained by the chiefs in the second; and taonga (property or valued possessions), which the chiefs are guaranteed ownership and control of, also in the second article. Few Māori had good understanding of either sovereignty or "governorship", as understood by 19th century Europeans, and so some academics, such as Moana Jackson, question whether Māori fully understood that they were ceding sovereignty to the British Crown.[perlu rujukan]

Furthermore, kāwanatanga is a loan translation from 'governorship' and was not part of the Māori language. The term had been used by Henry Williams in his translation of the Declaration of Independence of New Zealand which was signed by 35 northern Māori chiefs at Waitangi on 28 October 1835.[24] The Declaration of Independence of New Zealand had stated 'Ko te Kingitanga ko te mana i te w[h]enua' to describe 'all sovereign power and authority in the land'.[24]

There is considerable debate about what would have been a more appropriate term. Some scholars, notably Ruth Ross, argue that mana (prestige, authority) would have more accurately conveyed the transfer of sovereignty.[25] However, it has more recently been argued by others, for example Judith Binney, that mana would not have been appropriate. This is because mana is not the same thing as sovereignty, and also because no-one can give up their mana.[26]

The English language version recognises Māori rights to "properties", which seems to imply physical and perhaps intellectual property. The Māori version, on the other hand, mentions "taonga", meaning "treasures" or "precious things". In Māori usage the term applies much more broadly than the English concept of legal property, and since the 1980s courts have found that the term can encompass intangible things such as language and culture.[27][28][29] Even where physical property such as land is concerned, differing cultural understandings as to what types of land are able to be privately owned have caused problems, as for example in the foreshore and seabed controversy of 2003–04.

The pre-emption clause is generally not well translated, and many Māori apparently believed that they were simply giving the British Queen first offer on land, after which they could sell it to anyone.[perlu rujukan] Doubt has been cast on whether Hobson himself actually understood the concept of pre-emption. Another, less important, difference is that Ingarani, meaning England alone, is used throughout in the Māori version, whereas "the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland" is used in the first paragraph of the English.

The entire issue is further complicated by the fact that, at the time, Māori society was an oral rather than literate one. Māori present at the signing of the Treaty would have placed more value and reliance on what Hobson and the missionaries said, rather than the words of the actual Treaty.[30]

Māori beliefs and attitudes towards ownership and use of land were different from those prevailing in Britain and Europe. The chiefs saw themselves as 'kaitiaki' or guardians of the land, and would traditionally grant permission for the land to be used for a time for a particular purpose. Some may have thought that they were leasing the land rather than selling it, leading to disputes with the occupant settlers. A northern chief, Nopera Panakareao, also early on summarised his understanding of the Treaty as "the shadow of the land is to the Queen, but the substance remains to us.", even as a British official later remarked that the Māori would discover that the British had acquired "something more than the shadow.". Nopera's later reversed his earlier statement – feeling that the substance of the land had indeed gone to the Queen; only the shadow remained for the Māori.[31]

Kesan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada November 1840, sebuah perkenan diraja telah ditandatangani Ratu Victoria, establishing New Zealand sebagai sebuah Jajahan Mahkota yang berasingan daripada New South Wales dari Mei 1841.

Perjanjian ini langsung tidak diratifikasikan oleh Britain seterusnya tidak membawa apa-apa kusasa kepada New Zealand sehingga lebih satu abad kemudian pada 1975 dengan lulusnya Akta Perjanjian Waitangi. The Colonial Office and early New Zealand governors were initially fairly supportive of the Treaty as it gave them authority over both New Zealand Company settlers and Māori. As the settlers were granted representative and responsible government with the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852, the Treaty became less effective, although it was used to justify the idea that Waikato and Taranaki were rebels against the Crown in the wars of the 1860s. Court cases later in the 19th century, especially Wi Parata v the Bishop of Wellington (1877), established the principle that the Treaty was a 'legal nullity' which could be ignored by the courts and the government. This argument was supported by the claim that New Zealand had become a colony when annexed by proclamation in January 1840, before the treaty was signed. Furthermore, Hobson only claimed to have taken possession of the North Island by Treaty. The South Island he claimed for Britain by right of discovery, by observing that Māori were so sparse in the South Island, that it could be considered uninhabited.[perlu rujukan]

Despite this, Māori frequently used the Treaty to argue for a range of issues, including greater independence and return of confiscated and unfairly purchased land. This was especially the case from the mid-19th century, when they lost numerical superiority and generally lost control of most of the country.

However irrelevant in law, the Treaty returned to the public eye after the Treaty house and grounds were purchased by Governor-General Viscount Bledisloe in the early 1930s and donated to the nation. The dedication of the site as a national reserve in 1934 was probably the first major event held there since the 1840s. The profile of the Treaty was further raised by the centenary of 1940. For most of the 20th century, text books, government publicity and many historians touted it as the moral foundation of colonisation and to set race relations in New Zealand above those of colonies in North America, Africa and Australia. Its lack of legal significance in 1840 and subsequent breaches tended to be overlooked until the 1970s, when these issues were raised by Māori protest.

Kedudukan Perundangan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Perjanjian itu sendiri tidak pernah disahkan atau dikanunkan sebagai undang-undang statut di New Zealand, sungguhpun ia muncul dalam koleksi perjanjian berwibawa, dan kadang-kadang disebut dalam cebisan undang-undang yang khusus. Terdapat dua titik utama perdebatan perundangan mengenai Perjanjian: Sama ada atau tidak Perjanjian tersebut adalah cara yang Mahkota British mendapat kedaulatan ke atas New Zealand, dan Sama ada atau tidak Perjanjian tersebut mengikat Mahkota .

Sovereignty[sunting | sunting sumber]

Although the Treaty was considered to be Māori consenting to British sovereignty over the whole country, the actual proclamation of sovereignty was made by Hobson on 21 May 1840 (the North Island by treaty and the South by discovery – Hobson was unaware his agents were collecting signatures for the Treaty in the South Island at this stage).[13] This was in response to New Zealand Company attempts to establish a separate colony in Wellington. The proclamation was published four months after the signing of the Treaty, in the New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette issue of 19 June 1840, the proclamation "asserts on the grounds of Discovery, the Sovereign Rights of Her Majesty over the Southern Islands of New Zealand, commonly called 'The Middle Island' (South Island) and 'Stewart’s Island' (Stewart Island/Rakiura); and the Island, commonly called 'The Northern Island', having being ceded Sovereignty to Her Majesty."[32]

In the 1877 Wi Parata v Bishop of Wellington judgement, Prendergast argued that the Treaty was a 'simple nullity' in terms of transferring sovereignty from Māori to Britain.[33] This remained the legal orthodoxy until at least the 1970s.[34] Since then, legal commentators have argued that whatever the state of Māori government in 1840, the British had acknowledged Māori sovereignty with the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand in 1835.[35] Therefore, if both parties had agreed on the Treaty it was valid, in a pragmatic if not necessarily a legal sense.

There has been some popular acceptance of the idea that the Treaty transferred sovereignty since the early twentieth century. Popular histories of New Zealand and the Treaty often claimed that the Treaty was an example of British benevolence and therefore an honourable contract.[36]

The Waitangi Tribunal, in Te Paparahi o te Raki inquiry (Wai 1040)[37] is in the process of considering the Māori and Crown understandings of He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga / The Declaration of Independence 1835 and Te Tiriti o Waitangi / the Treaty of Waitangi 1840. This aspect of the inquiry raises issues as to the nature of sovereignty and whether the Maori signatories to the Treaty of Waitangi intended to transfer sovereignty.[38]

Binding on the Crown?[sunting | sunting sumber]

While the above issue is mostly academic, since the Crown does have sovereignty in New Zealand, the question of whether the Crown is bound by the Treaty has been hotly contested since 1840. This has been a point of a number of court cases:

- R v Symonds (1847). The Treaty was found to be binding on the Crown.

- Wi Parata v Bishop of Wellington (1877). Judge James Prendergast called the Treaty ‘a simple nullity’ and claimed that it was neither a valid treaty nor binding on the Crown. Although the Treaty’s status was not a major part of the case, Prendergast’s judgment on the Treaty’s validity was considered definitive for many decades.

- Te Heuheu Tukino v Aotea District Maori Land Board (1938). The Treaty was seen as valid in terms of the transfer of sovereignty, but the judge ruled that as it was not part of New Zealand law it was not binding on the Crown.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney General (1987). Also known as the SOE (State Owned Enterprises) case, this defined the "principles of the Treaty". The State Owned Enterprises Act stated that nothing in the Act permitted the government to act inconsistently with the principles of the Treaty, and the proposed sale of government assets was found to be in breach of these. This case established the principle that if the Treaty is mentioned in a piece of legislation, it takes precedence over other parts of that legislation should they come into conflict.

- New Zealand Maori Council v Attorney General (1990). This case concerned FM radio frequencies and found that the Treaty could be relevant even concerning legislation which did not mention it.[39]

Since the late 1980s the Treaty has become much more legally important. However because of uncertainties about its meaning and translation, it still does not have a firm place in New Zealand law or jurisprudence. Another issue is whether the Crown in Right of New Zealand is bound. The separate New Zealand Crown was created when New Zealand adopted of the Statute of Westminster in 1947, which granted legislative independence to New Zealand and created the Crown in Right of New Zealand.[40] Dr Martyn Finlay rejected this contention.[40]

Legislation[sunting | sunting sumber]

The English version of the Treaty appeared as a schedule to the Waitangi Day Act 1960, but this did not technically make it a part of statute law. The Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 established the Waitangi Tribunal, but this initially had very limited powers. The Act was amended in 1985 to increase the Tribunal membership and enable it to investigate Treaty breaches back to 1840. The membership was further increased in another amendment, in 1988.

Although the Treaty has never been incorporated into New Zealand municipal law, its provisions were first incorporated into legislation as early as the Land Claims Ordinance 1841 and the Native Rights Act 1865.[41] Later the Treaty was incorporated into New Zealand law in the State Owned Enterprises Act 1986. Section 9 of the Act said that nothing in the Act permitted the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. This allowed the courts to consider the Crown's actions in terms of compliance with the Treaty (see below, "The Principles of the Treaty"). Contemporary legislation has followed suit, giving the Treaty an increased legal importance.

The Bill of Rights White Paper proposed that the Treaty be entrenched in the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, however this proposal was never carried through to the legislation, with many Māori being concerned that this would relegate the Treaty to a lesser position, and enable the electorate (who under the original Bill of Rights would be able to repeal certain sections by referendum) to remove the Treaty from the Bill of Rights altogether.

In response to a backlash against the Treaty, politician Winston Peters the 13th Deputy Prime Minister of New Zealand (and founder of the New Zealand First Party) and others have campaigned to remove vague references to the Treaty from New Zealand law, although the New Zealand Māori Council case of 1990 indicated that even if this does happen, the Treaty may still be legally relevant.

"Principles of the Treaty"[sunting | sunting sumber]

The "Principles of the Treaty" are often mentioned in contemporary politics.[42] They originate from the famous case brought in the High Court by the New Zealand Māori Council (New Zealand Māori Council v. Attorney-General[43]) in 1987. There was great concern at that time that the ongoing restructuring of the New Zealand economy by the then Fourth Labour Government, specifically the transfer of assets from former Government departments to State-owned enterprises. Because the state-owned enterprises were essentially private firms owned by the government, they would prevent assets which had been given by Māori for use by the state from being returned to Māori by the Waitangi Tribunal. The Māori Council sought enforcement of section 9 of the State Owned Enterprises Act 1986 "Nothing in this Act shall permit the Crown to act in a manner that is inconsistent with the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi".

The Court of Appeal, in a judgment of its then President Sir Robin Cooke, decided upon the following Treaty principles:

- The acquisition of sovereignty in exchange for the protection of rangatiratanga.

- The Treaty established a partnership, and imposes on the partners the duty to act reasonably and in good faith.

- The freedom of the Crown to govern.

- The Crown’s duty of active protection.

- The duty of the Crown to remedy past breaches.

- Māori to retain rangatiratanga over their resources and taonga and to have all the privileges of citizenship.

- Duty to consult.

In 1989, the Fourth Labour Government responded by adopting the following "Principles for Crown Action on the Treaty of Waitangi":

- Principle of government or the kawanatanga principle

- Article 1 gives expression to the right of the Crown to make laws and its obligation to govern in accordance with constitutional process. This sovereignty is qualified by the promise to accord the Māori interests specified in article 2 an appropriate priority. This principle describes the balance between articles 1 and 2: the exchange of sovereignty by the Māori people for the protection of the Crown. It was emphasised in the context of this principle that ‘the Government has the right to govern and make laws’.

- Principle of self-management (the rangatiratanga principle)

- Article 2 guarantees to Māori hapū (tribes) the control and enjoyment of those resources and taonga that it is their wish to retain. The preservation of a resource base, restoration of tribal self-management, and the active protection of taonga, both material and cultural, are necessary elements of the Crown’s policy of recognising rangatiratanga.

The Government also recognised the Court of Appeal’s description of active protection, but identified the key concept of this principle as a right for iwi to organise as iwi and, under the law, to control the resources they own. - Principle of equality

- Article 3 constitutes a guarantee of legal equality between Māori and other citizens of New Zealand. This means that all New Zealand citizens are equal before the law. Furthermore, the common law system is selected by the Treaty as the basis for that equality, although human rights accepted under international law are also incorporated. Article 3 has an important social significance in the implicit assurance that social rights would be enjoyed equally by Māori with all New Zealand citizens of whatever origin. Special measures to attain that equal enjoyment of social benefits are allowed by international law.

- Principle of reasonable cooperation

- The Treaty is regarded by the Crown as establishing a fair basis for two peoples in one country. Duality and unity are both significant. Duality implies distinctive cultural development while unity implies common purpose and community. The relationship between community and distinctive development is governed by the requirement of cooperation, which is an obligation placed on both parties by the Treaty. Reasonable cooperation can only take place if there is consultation on major issues of common concern and if good faith, balance, and common sense are shown on all sides. The outcome of reasonable cooperation will be partnership.

- Principle of redress

- The Crown accepts a responsibility to provide a process for the resolution of grievances arising from the Treaty. This process may involve courts, the Waitangi Tribunal, or direct negotiation. The provision of redress, where entitlement is established, must take account of its practical impact and of the need to avoid the creation of fresh injustice. If the Crown demonstrates commitment to this process of redress, it will expect reconciliation to result.

The "Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill" was introduced to the New Zealand Parliament in 2005 as a private member's bill by New Zealand First MP Doug Woolerton. "This bill eliminates all references to the expressions "the principles of the Treaty", "the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi" and the "Treaty of Waitangi and its principles" from all New Zealand Statutes including all preambles, interpretations, schedules, regulations and other provisos included in or arising from each and every such Statute".[44] The bill failed to pass its second reading in November 2007.[45]

Claims for redress[sunting | sunting sumber]

During the late 1960s and 1970s, the Treaty of Waitangi became the focus of a strong Māori protest movement which rallied around calls for the government to "honour the treaty" and to "redress treaty grievances." Māori expressed their frustration about continuing violations of the treaty and subsequent legislation by government officials, as well as inequitable legislation and unsympathetic decisions by the Māori Land Court alienating Māori land from its Māori owners.

During the early 1990s, the government began to negotiate settlements of historical (pre-1992) claims. Setakat September 2008[kemas kini], there have been 23 such settlements of various sizes, totalling approximately $700 million. Settlements generally include financial redress, a formal Crown apology for breaches of the Treaty, and recognition of the group's cultural associations with various sites.

Public opinion[sunting | sunting sumber]

While during the 1990s there was broad agreement between major political parties that the settlement of historical claims was appropriate, in recent years it has become the subject of heightened debate. Claims of a "Treaty of Waitangi Grievance Industry", which profits from making frivolous claims of violations of the Treaty of Waitangi, have been made by a number of political figures, including former National Party leader Don Brash in his 2004 "Orewa Speech".[6] Although claims relating to loss of land by Māori are relatively uncontroversial, debate has focused on claims that fall outside common law concepts of ownership, or relate to technologies developed since colonisation. Examples include the ownership of the radio spectrum and the protection of the Māori language.

The New Zealand Election Study of 2008 found of the 2,700 voting age New Zealanders surveyed, 37.4% wanted the Treaty removed from New Zealand law, 19.7% were neutral and 36.8% wanted the Treaty kept in law. 39.7% agreed Māori deserved compensation, 15.7% were neutral and 41.2% disagreed.[46]

Rujukan[sunting | sunting sumber]

- ^ "Meaning of the Treaty". Waitangi Tribunal. 2011. Dicapai pada 12 Julai 2011.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi – Te Tiriti o Waitangi". Archives New Zealand. Dicapai pada 10 Ogos 2011.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi". Waitangi Tribunal. Dicapai pada 10 Ogos 2011.

- ^ "The Treaty in practice: The Treaty debated". nzhistory.net.nz. Dicapai pada 10 Ogos 2011.

- ^ "Treaty of Waitangi – Meaning". Waitangi Tribunal. Dicapai pada 10 Ogos 2011.

- ^ a b Dr Donald Brash (26 Mac 2004). "Orewa Speech—Nationhood". Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 9 Februari 2013. Dicapai pada 20 Mac 2011.

- ^ a b c Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-301867-1.

- ^ Binney, Judith (2007). Te Kerikeri 1770–1850, The Meeting Pool, Bridget Williams Books (Wellington) in association with Craig Potton Publishing (Nelson). ISBN 1-877242-38-1. Chapter 13, "The Māori Leaders' Assembly, Kororipo Pā, 1831" karya Manuka Henare, m.s 114–116.

- ^ Paul Moon (5 Oktober 2010). "Paul Moon: Agreement long ago left in tatters".

- ^ a b Paul Moon, penyunting (2010). New Zealand Birth Certificates – 50 of New Zealand's Founding Documents. AUT Media. ISBN 978-0-9582997-1-8.

- ^ "Ships, Famous. Tory". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand.

- ^ "A Toe-Hold at Akaroa – French Colonial Aspirations in Nouvelle-Zéalande". Dicapai pada 30 Jun 2009.

- ^ a b Morag McDowell & Duncan Webb. The New Zealand Legal System. LexisNexis.

- ^ Paul Moon (14 Ogos 2009). "Urge to 'civilise' behind NZ's quiet conception". The New Zealand Herald. Dicapai pada 14 Ogos 2009.

- ^ Scholefield, G. (1930). Captain William Hobson. pp. 202–203. (Instructions from Lord Normanby to Captain Hobson – dated 14 August 1839)

- ^ "Today in History". NZHistory.

- ^ Wises New Zealand Guide, 7th Edition, 1979. p. 499.

- ^ King, Marie. (1949). A Port in the North: A Short History of Russell. p. 38.

- ^ "Paul Moon: Hope for watershed in new Treaty era". The New Zealand Herald. 13 Januari 2010. Dicapai pada 15 Januari 2010.

- ^ a b Colenso, William (1890). The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: By Authority of George Didsbury, Government Printer. Dicapai pada 31 Ogos 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Orange, Claudia (2004). An Ilustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 1-877242-16-0.

- ^ P285-292 Treaty of Waitangi.C Orange.Bridget Wiliams Books. 2004

- ^ <P298-302 Treaty of Waitangi. C Orange. Bridget Williams Books 2004>

- ^ a b "The Declaration of Independence". Translation from Archives New Zealand , New Zealand History online. Dicapai pada 18 Ogos 2010.

- ^ Ross, R. M. (1972). "Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Texts and Translations". New Zealand Journal of History. 6 (2): 139–141.

- ^ Binney, Judith (1989). "The Maori and the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi". Towards 1990: Seven Leading Historians Examine Significant Aspects of New Zealand History. m/s. 20–31.

- ^ The Maori Broadcasting Claim: A Pakeha Economist’s Perspective. Brian Easton. 1990. Dicapai pada 1 September 2011.

- ^ Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on Claims Concerning the Allocation of Radio Frequencies (Wai 26). Waitangi Tribunal. 1990. Dicapai pada 1 September 2011.

- ^ Radio Spectrum Management and Development Final Report (Wai 776). Waitangi Tribunal. 1999. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 Mac 2012. Dicapai pada 1 September 2011.

- ^ Belich, James (1996), Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders from Polynesian Settlement to the End of the Nineteenth Century, m.s 195–6.

- ^ From Zero to 360 degrees: Cultural Ownership in a Post-European Age Diarkibkan 2006-10-04 di Wayback Machine – Mane-Wheoki, Jonathan; University of Canterbury, International Council of Museums, Council for Education and Cultural Action Conference, New Zealand, via the Christchurch Art Gallery website. Dicapai pada 27 Oktober 2009.

- ^ "New Zealand Advertiser and Bay Of Islands Gazette, 19 June 1840". Hocken Library. Dicapai pada 22 April 2010.

- ^ Wi Parata v Bishop of Wellington (1877) 3 NZ Jurist Reports (NS) Supreme Court, p72.

- ^ Helen Robinson, 'Simple Nullity or Birth of Law and Order? The Treaty of Waitangi in Legal and Historiographical Discourse from 1877 to 1970', NZ Universities Law Review, 24, 2 (2010), p262.

- ^ Peter Adams (1977). Fatal necessity: British intervention in New Zealand, 1830–1847. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

- ^ Robinson, 'Simple Nullity or Birth of Law and Order?', p264.

- ^ "Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) inquiry". Waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 11 Oktober 2011. Dicapai pada 1 November 2011.

- ^ Paul Moon (2002) Te Ara Ki Te Tiriti: The Path to the Treaty of Waitangi

- ^ Durie, Mason (1998), Te Mana, Te Kawanatanga: The Politics of Maori Self-Determination, pp. 179–84.

- ^ a b New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, Volume 279. Clerk of the House of Representatives. 17 October – 27 November. Check date values in:

|date=(bantuan) - ^ Jamieson, Nigel J. (2004), Talking Through the Treaty – Truly a Case of Pokarekare Ana or Troubled Waters, New Zealand Association for Comparative Law Yearbook 10

- ^ He Tirohanga ō Kawa ki te Tiriti o Waitangi: a guide to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi as expressed by the Courts and the Waitangi Tribunal. Te Puni Kokiri. 2001. ISBN 0-478-09193-1. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 22 Februari 2008. Dicapai pada 8 Februari 2007.

- ^ [1987] 1 NZLR 641.

- ^ "Doug Woolerton's Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill". New Zealand First. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 1 Julai 2007. Dicapai pada 13 Jun 2007.

- ^ "New Zealand Parliament - Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi Deletion Bill". Parliament.nz. 7 November 2007. Dicapai pada 1 November 2011.

- ^ "Part D – What are Your Opinions?". New Zealand Election Study. 2008.

baca lanjut[sunting | sunting sumber]

- Adams, Peter (1977). Fatal Necessity: British Intervention in New Zealand 1830–1847. Auckland: Auckland University Press. ISBN 0-19-647950-9.

- Durie, Mason (1998). Te Mana, Te Kāwanatanga; The Politics of Māori Self-Determination. Auckland: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558367-1.

- Moon, Paul (2002). Te ara kī te Tiriti (The Path to the Treaty of Waitangi). Auckland: David Ling. ISBN 0-908990-83-9.

- Orange, Claudia (1989). The Story of a Treaty. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-641053-8.

- Orange, Claudia (1990). An Ilustrated History of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-442169-9.

- Scott, Dick (1975). Ask That Mountain: The Story of Parihaka. Auckland: Heinemann. ISBN 0-7900-0190-X.

- Walker, Ranginui (2004). Ka whawhai tonu matou (Struggle without End) (ed. rev.). Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-301945-7.

- Simpson, Miria. (1990). Nga Tohu O Te Tiriti/Making a Mark: The signatories to the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: National Library of New Zealand.

- Buick, T Lindsay (1916). The Treaty of Waitangi: or How New Zealand became a British Colony (the first substantial work on the Treaty)

Pautan luar[sunting | sunting sumber]

- Signatories to the Treaty of Waitangi

- Laman maklumat rasmi mengenai Perjanjian Waitangi

- Rencana mengenai perjanjian ini daripada Kementerian Budaya dan Warisan New Zealand

- Office of Treaty Settlements

- Biography of Moka Te Kainga-mataa

- The Patuone Website

- "Was there a Treaty of Waitangi?". Essay by independent scholar and NZ Listener columnist Brian Easton

- Tribunal Waitangi

- Teks asal Perjanjian Waitangi dalam bahasa-bahasa Inggeris dan Māori Diarkibkan 2005-07-18 di Wayback Machine

- New Zealand Legislation Diarkibkan 2003-10-02 di Wayback Machine

- Archives New Zealand site

- The Trail of Waitangi – original research

- The "Littlewood Treaty": An Appraisal of Texts and Interpretations Diarkibkan 2007-08-10 di Wayback Machine Review of historical literature relating to the Littlewood Treaty.

- Legislative Violations of the Treaty (1840–1997) – at the Network Waitangi Otautahi

- Waitangi Treaty Ground website

- Guna tarikh dmy dari August 2011

- Rencana yang memerlukan rujukan tambahan dari February 2011

- Semua rencana dengan kenyataan tidak bersumber dari February 2011

- Semua rencana yang mengandungi kenyataan yang mungkin lapuk dari September 2008

- Sejarah New Zealand

- Perjanjian New Zealand

- Perjanjian United Kingdom (1801–1922)

- Perjanjian Koloni New Zealand