Bahasa isyarat

Bahasa isyarat merupakan bahasa yang bergantung kepada kaedah komunikasi yang tidak menggunakan suara, tetapi pergerakan tangan, badan dan bibir untuk menyampaikan maklumat bermaksud apa yang difikiran seorang "penutur" sepertimana bahasa yang dituturkan melalui percakapan. Bahasa ini dikembangkan dan dimanfaatkan dalam kalangan masyarakat yang pekak tuli, saudara-mara terdekat serta jurubahasa isyarat.

Terdapat 150 jenis bahasa isyarat yang dicatatkan terguna seluruh dunia (menurut edisi Ethnologue 2021)[1] oleh para penghidap kepekakan setempat. Terdapat bahasa isyarat yang berjaya diiktiraf dalam pelbagai peringkat[2] sama ada sebagai satu bahasa yang sahih (seperti Bahasa Isyarat British) , bahasa rasmi (seperti Bahasa Isyarat New Zealand) dan Bahasa Isyarat Malaysia; ada juga bahasa isyarat masih belum mendapat pengiktirafan langsung.

Ciri utama[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pengungkapan dalam sesebuah bahasa isyarat menggunakan pola isyarat dihantar (komunikasi manual, bahasa badan) untuk memberi makna—serentak dengan gabungan bentuk tangan, orientasi dan pergerakkan tangan, lengan, atau badan, dan raut muka untuk menggambarkan dengan licin pemikiran penutur.

Tatabahasa spatial amat berbeza dengan tata bahasa pertuturan.[3][4] Sebagai contoh, berikut adalah tatabahasa Bahasa Isyarat Malaysia yang biasa digunakan oleh komuniti Pekak di Malaysia;

s - subjek, o- objek, v- verb (perbuatan)

- ov - nasi makan...

- vo - makan nasi...

- sov - ali nasi makan...

- svo - ali makan nasi...

- ovs - nasi ali makan...

Sejarah bahasa isyarat[sunting | sunting sumber]

Salah satu rekod penulisan terawal bahasa isyarat berlaku pada abad ke lima BC, di Cratylus oleh Plato, di mana Socrates berkata: "Sekiranya kita tidak memiliki suara atau lidah, dan ingin menggambarkan sesuatu semasa sendiri, tidakkah kita akan cuba membuat isyarat dengan menggerakkan tangan, kepala, dan seluruh badan kita, sebagaimana mereka yang pekak lakukannya sekarang?" [5] Ia kelihatannya kelompok orang pekak telah menggunakan bahasa isyarat sepanjang sejarah.

Seperti bahasa tuturan, bahasa isyarat berbeza mengikut lokasi dan rantau. Namun, kefahaman menyaling adalah lebih mudah antara dua bahasa isyarat berbeza berbanding dengan dua bahasa pertuturan yang berbeza.

Kemajuan bahasa isyarat di dunia boleh dibuktikan dengan kemunculan dan perkembangan dalam puisi bahasa isyarat dan juga persembahan pentas yang lain.

Di Malaysia, Bahasa Isyarat Malaysia (BIM) telah diiktiraf sebagai bahasa rasmi untuk Komuniti Pekak. Ianya telah mendapat persetujuan dari Ahli Dewan Rakyat dan termaktub dalam Akta OKU 2008.

Rujukan[sunting | sunting sumber]

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., penyunting (2021), "Sign language", Ethnologue: Languages of the World (ed. 24th), SIL International, dicapai pada 2021-05-15

- ^ Wheatley, Mark & Annika Pabsch (2012). Sign Language Legislation in the European Union – Edition II. European Union of the Deaf.

- ^ Stokoe, William C. (1976). Dictionary of American Sign Language on Linguistic Principles. Linstok Press. ISBN 0-932130-01-1.

- ^ Stokoe, William C. (1960). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in linguistics: Occasional papers (No. 8). Buffalo: Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo.

- ^ Bauman, Dirksen (2008). Open your eyes: Deaf studies talking. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816646198.

Bibliografi[sunting | sunting sumber]

- Aronoff, Mark; Meir, Irit; Sandler, Wendy (2005). "The Paradox of Sign Language Morphology". Language. 81 (2): 301–344. doi:10.1353/lan.2005.0043.

- Branson, J., D. Miller, & I G. Marsaja. (1996). "Everyone here speaks sign language, too: a deaf village in Bali, Indonesia." In: C. Lucas (ed.): Multicultural aspects of sociolinguistics in deaf communities. Washington, Gallaudet University Press, pp. 39–5.

- Canlas, Loida (2006). "Laurent Clerc: Apostle to the Deaf People of the New World." The Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, Gallaudet University.[1] Diarkibkan 2009-01-13 di Wayback Machine

- Deuchar, Margaret (1987). "Sign languages as creoles and Chomsky's notion of Universal Grammar." Essays in honor of Noam Chomsky, 81–91. New York: Falmer.

- Emmorey, Karen; & Lane, Harlan L. (Eds.). (2000). The signs of language revisited: An anthology to honor Ursula Bellugi and Edward Klima. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-3246-7.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1974). "Sign language and linguistic universals." Actes du Colloque franco-allemand de grammaire générative, 2.187-204. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Fischer, Susan D. (1978). "Sign languages and creoles". Siple. 1978: 309–31.

- Frishberg, Nancy (1987). "Ghanaian Sign Language." In: Cleve, J. Van (ed.), Gallaudet encyclopaedia of deaf people and deafness. New York: McGraw-Gill Book Company.

- Goldin-Meadow, Susan, 2003, The Resilience of Language: What Gesture Creation in Deaf Children Can Tell Us About How All Children Learn Language, Psychology Press, a subsidiary of Taylor & Francis, New York, 2003

- Gordon, Raymond, ed. (2008). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th edition. SIL International, ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6, ISBN 1-55671-159-X. Web version.[2] Sections for primary sign languages [3] and alternative ones [4].

- Groce, Nora E. (1988). Everyone here spoke sign language: Hereditary deafness on Martha's Vineyard. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-27041-X.

- Healy, Alice F. (1980). Can Chimpanzees learn a phonemic language? In: Sebeok, Thomas A. & Jean Umiker-Sebeok, eds, Speaking of apes: a critical anthology of two-way communication with man. New York: Plenum, 141–143.

- Hewes, Gordon W. (1973). "Primate communication and the gestural origin of language". Current Anthropology. 14: 5–32. doi:10.1086/201401.

- Johnston, Trevor A. (1989). Auslan: The Sign Language of the Australian Deaf community. The University of Sydney: unpublished Ph.D. dissertation.[5]

- Kamei, Nobutaka (2004). The Sign Languages of Africa, "Journal of African Studies" (Japan Association for African Studies) Vol.64, March, 2004. [NOTE: Kamei lists 23 African sign languages in this article].

- Kegl, Judy (1994). "The Nicaraguan Sign Language Project: An Overview." Signpost 7:1.24–31.

- Kegl, Judy, Senghas A., Coppola M (1999). "Creation through contact: Sign language emergence and sign language change in Nicaragua." In: M. DeGraff (ed), Comparative Grammatical Change: The Intersection of Language Acquisistion, Creole Genesis, and Diachronic Syntax, pp. 179–237. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kegl, Judy (2004). "Language Emergence in a Language-Ready Brain: Acquisition Issues." In: Jenkins, Lyle, (ed), Biolinguistics and the Evolution of Language. John Benjamins.

- Kendon, Adam. (1988). Sign Languages of Aboriginal Australia: Cultural, Semiotic and Communicative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kimura, Doreen (1993). Neuromotor Mechanisms in Human Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1979). The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-80795-2.

- Kolb, Bryan, and Ian Q. Whishaw (2003). Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 5th edition, Worth Publishers.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1940). "Stimulus diffusion". American Anthropologist. 42: 1–20. doi:10.1525/aa.1940.42.1.02a00020.

- Krzywkowska, Grazyna (2006). "Przede wszystkim komunikacja", an article about a dictionary of Hungarian sign language on the internet (Polonès).

- Lane, Harlan L. (Ed.). (1984). The Deaf experience: Classics in language and education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19460-8.

- Lane, Harlan L. (1984). When the mind hears: A history of the deaf. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-50878-5.

- Madell, Samantha (1998). Warlpiri Sign Language and Auslan - A Comparison. M.A. Thesis, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.[6]

- Madsen, Willard J. (1982), Intermediate Conversational Sign Language. Gallaudet University Press. ISBN 978-0913580790.

- Nakamura, Karen. (1995). "About American Sign Language." Deaf Resourec Library, Yale University.[7]

- Newman, A. J.; Bavelier, D; Corina, D; Jezzard, P; Neville, HJ; dll. (2002). "A Critical Period for Right Hemisphere Recruitment in American Sign Language Processing". Nature Neuroscience. 5 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1038/nn775. PMID 11753419. Explicit use of et al. in:

|first1=(bantuan) - O'Reilly, S. (2005). Indigenous Sign Language and Culture; the interpreting and access needs of Deaf people who are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander in Far North Queensland. Sponsored by ASLIA, the Australian Sign Language Interpreters Association.

- Padden, Carol; & Humphries, Tom. (1988). Deaf in America: Voices from a culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-19423-3.

- Poizner, Howard; Klima, Edward S.; & Bellugi, Ursula. (1987). What the hands reveal about the brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Premack, David, & Ann J. Premack (1983). The mind of an ape. New York: Norton.

- Premack, David (1985). "'Gavagai!' or the future of the animal language controversy". Cognition. 19 (3): 207–296. doi:10.1016/0010-0277(85)90036-8. PMID 4017517.

- Sacks, Oliver W. (1989). Seeing voices: A journey into the world of the deaf. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06083-0.

- Sandler, Wendy (2003). Sign Language Phonology. In William Frawley (Ed.), The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Linguistics.[8]

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2001). Natural sign languages. In M. Aronoff & J. Rees-Miller (Eds.), Handbook of linguistics (pp. 533–562). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-20497-0.

- Sandler, Wendy; & Lillo-Martin, Diane. (2006). Sign Language and Linguistic Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Stiles-Davis, Joan; Kritchevsky, Mark; & Bellugi, Ursula (Eds.). (1988). Spatial cognition: Brain bases and development. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-0046-8; ISBN 0-8058-0078-6.

- Stokoe, William C. (1960, 1978). Sign language structure: An outline of the visual communication systems of the American deaf. Studies in linguistics, Occasional papers, No. 8, Dept. of Anthropology and Linguistics, University of Buffalo. 2d ed., Silver Spring: Md: Linstok Press.

- Stokoe, William C. (1974). Classification and description of sign languages. Current Trends in Linguistics 12.345–71.

- Valli, Clayton, Ceil Lucas, and Kristin Mulrooney. (2005) Linguistics of American Sign Language: An Introduction. 4th Ed. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Van Deusen-Phillips S.B., Goldin-Meadow S., Miller P.J., 2001. Enacting Stories, Seeing Worlds: Similarities and Differences in the Cross-Cultural Narrative Development of Linguistically Isolated Deaf Children, Human Development, Vol. 44, No. 6.

- Wittmann, Henri (1980). "Intonation in glottogenesis." The melody of language: Festschrift Dwight L. Bolinger, in: Linda R. Waugh & Cornelius H. van Schooneveld, 315–29. Baltimore: University Park Press.[9]

- Wittmann, Henri (1991). "Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement." Revue québécoise de linguistique théorique et appliquée 10:1.215–88.[10]

Pautan luar[sunting | sunting sumber]

| Wikimedia Commons mempunyai media berkaitan Bahasa isyarat |

| Wikibuku mempunyai sebuah buku berkenaan topik: Bahasa isyarat |

Note: the articles for specific sign languages (e.g. ASL or BSL) may contain further external links, e.g. for learning those languages.

- American Sign Language (ASL) resource site.

- A DeafWiki free-content encyclopedia of deaf and hard hearing Diarkibkan 2016-10-02 di Wayback Machine

- Signes du Monde, directory for all online Sign Languages dictionaries (Perancis) / (Inggeris)

- List Serv for Sign Language Linguistics Diarkibkan 2004-10-13 di Wayback Machine

- The MUSSLAP Project Multimodal Human Speech and Sign Language Processing for Human-Machine Communication.

- Publications of the American Sign Language Linguistics Research Project

- Sign language among North American Indians compared with that among other peoples and deaf-mutes, by Garrick Mallery from Project Gutenberg. A first annual report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1879–1880

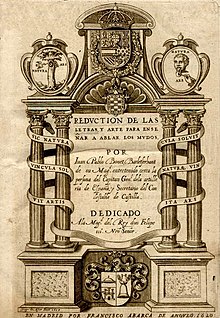

- Pablo Bonet, J. de (1620) http://bibliotecadigitalhispanica.bne.es:80/webclient/DeliveryManager?application=DIGITOOL-3&owner=resourcediscovery&custom_att_2=simple_viewer&pid=180918 Diarkibkan 2009-12-21 di Wayback Machine, Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (BNE).