Bukit Kuil

| Bukit Kuil | |

|---|---|

| הַר הַבַּיִת, Har HaBayit الحرم الشريف, al-Ḥaram ash-Šarīf, Perkarangan Suci | |

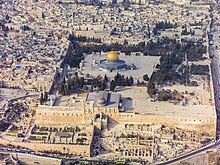

Sudut pandang selatan dari Bukit Kuil | |

| Titik tertinggi | |

| Ketinggian | 740 m (2,430 ka) |

| Koordinat | 31°46′40.7″N 35°14′8.9″E / 31.777972°N 35.235806°EKoordinat: 31°46′40.7″N 35°14′8.9″E / 31.777972°N 35.235806°E |

| Geografi | |

| Lokasi | Baitulmaqdis |

| Induk banjaran | Pergunungan Hebron |

| Geologi | |

| Jenis gunung | Meleke[1] |

| Sebahagian daripada siri berkaitan |

| Baitulmaqdis |

|---|

|

Bukit Kuil, atau kadang kala disebut perkarangan suci al-Quds[2] ialah sebuah bukit di Kota Lama Baitulmaqdis yang menjadi tapak suci bagi tiga agama samawi: Islam, Kristian dan Yahudi, untuk beribu-ribu tahun.[3][4] Bukit ini dalam teori kepercayaan Yahudi ialah sebagaian daripada kawasan pergunungan Moriah.[5]

Medan lapang bukit ini dikelilingi oleh dinding penahan tanah (termasuklah Tembok Ratapan), pada asalnya dibina oleh Raja Herodus pada awal kurun pertama sebelum Masihi, dan ditambah kemudiannya oleh pemerintah kawasan ini termasuklah era Rom Timur, pemerintah awal Muslim, Mamluk, dan Usmaniyah, dan boleh dicapai menerusi sebelah gerbang, sepuluh digunakan untuk Muslim dan satu untuk bukan Muslim.[6] Kawasan lamannya juga dikelilingi di utara dan barat dengan dua buah riwaq era Mamluk dan empat menara. Ia dikuasai oleh dua buah binaan yang pada asalnya dibina pada zaman Khalifah Al-Rasyiddan awal pemerintahan Umaiyah selepas pembukaan kota ini pada 637 Masihi:[7] ruang solat utama Masjid Al-Aqsa dan Kubah al-Sakhrah, berdekatan dengan titik tengah bukit ini, yang mana menjadi binaan Islam tertua di dunia.

Bukit Kuil ialah tempat di mana beberapa kuil Yahudi silam dipercayai didirikan, yang mana ditempatkan di situ, berhampiran Tembok Ratapan, menjadi tapak paling suci dalam agama Yahudi.[8][9][a][11] Menurut sumber lama Yahudi,[12] Kuil Pertama telah dibina oleh Raja Solomon, putera Raja David, pada 957 SM, dan dimusnahkan oleh Empayar Babylon Baru, bersama-sama Jerusalem, pada 587 SM. Tiada bukti arkeologi ditemui bagi mengesahkan perkara ini, tetapi penggalian saintifik telah dihadkan disebabkan sensitiviti agama.[13][14][15][16] Kuil Kedua yang dibina di bawah naungan Zerubabel pada 516 SM, telah diubah suai oleh Raja Herodus, dan dimusnahkan oleh Empayar Rom pada 70 Masihi. Sumber Yahudi Ortodoks mengekalkan ia di situ dan kuil ketiga dan terakhir akan dibina ketika kedatangan Messiah.[17] Bukit Kuil ialah tempat Yahudi berkumpul bagi sembahyang. Sikap Yahudi mengenai masuk ke tempat ini berubah-ubah. Disebabkan kesuciannya yang malampau, banyak Yahudi tidak akan berjalan ke Bukit ini sendiri, bagi mengelakkan memasuki secara tidak sengaja ke kawasan Ruang Maha Suci didirikan, memandangkan, menurut undang-undang rabai, di sana terdapat beberapa tempat penurunan wahyu di tapak tersebut.[18][19][20]

Rujukan[sunting | sunting sumber]

- ^ "New Jerusalem Finds Point to the Temple Mount". cbn.com.

- ^ Kedar, Benjamin (2012). "Rival Conceptualizations of a Single Space: Jerusalem's sacred esplanade". Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313532683. "The author intends … to deal with a single space—the space which, if we wish to use a strictly neutral term, may be called ‘Jerusalem’s sacred esplanade’."

- ^ Kedar, Benjamin (2012). "Rival Conceptualizations of a Single Space: Jerusalem's sacred esplanade". Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313532683. "The author intends … to deal with a single space – the space which, if we wish to use a strictly neutral term, may be called ‘Jerusalem’s sacred esplanade’."

- ^ Weaver, A.E. (2018). Inhabiting the Land: Thinking Theologically about the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict. Cascade Companions. Wipf and Stock Publishers. m/s. 77. ISBN 978-1-4982-9431-7. Dicapai pada 2022-05-21.

The conflict about sovereignty over Jerusalem encompasses conflict over control of the Holy Esplanade, called al-Haram ash-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary) by Muslims and Har HaBayit (the Temple Mount) by Jews.

- ^ Kalimi, Isaac (1990). "The Land of Moriah, Mount Moriah, and the Site of Solomon's Temple in Biblical Historiography". The Harvard Theological Review. 83 (4): 345–362. ISSN 0017-8160.

- ^ "Temple Mount/Al Haram Ash Sharif". Lonely Planet. Dicapai pada April 17, 2018.

- ^ Nicolle, David (1994). Yarmuk AD 636: The Muslim Conquest of Syria. Osprey Publishing.

- ^ Marshall J., Breger; Ahimeir, Ora (2002). Jerusalem: A City and Its Future. Syracuse University Press. m/s. 296. ISBN 978-0-8156-2912-2. OCLC 48940385.

- ^ Cohen-Hattab, Kobi; Bar, Doron (2020). The Western Wall: The Dispute over Israel's Holiest Jewish Site, 1967–2000 (dalam bahasa Inggeris). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-43133-1.

- ^ Gonen 2003, m/s. 4.

- ^ Sporty, Lawrence D. (1990). "The Location of the Holy House of Herod's Temple: Evidence from the Pre-Destruction Period". The Biblical Archaeologist. 53 (4): 194–204. doi:10.2307/3210164. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210164. S2CID 224797947.

The holy house has most commonly assumed to be located on the same spot as the Moslem holy structure known as the Dome of the Rock. This assumption has been held for centuries for the following reasons: The rock out-cropping under the Dome of the Rock is the main natural feature within the Haram enclosure; the Dome of the Rock is centrally located within the esplanade, and, at 2,440 feet above sea level, the Dome of the Rock is one of the highests point within the area.

- ^ 2 Chron. 3:1–2Template:Bibleverse with invalid book.

- ^ Gibson & Jacobson 1994 "Religious sensitivities have discouraged scientific investigation of subterranean features within the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, which incorporates the area of the ancient Temple Mount. In consequence, the mystery of this sacred place has been heightened, providing fertile ground for flights of fancy concerning the two Jewish temples that formerly occupied the site. Even serious scholars have had to make do with hypotheses concerning the position and layout of these ancient complexes… However, for a brief period in the second half of the nineteenth century a handful of intrepid European explorers, in particular Charles Wilson, Charles Warren, Claude Regnier Conder, and Conrad Schick, succeeded in lifting this veil of secrecy and visited many of the underground chambers that pepper this sacred site."

- ^ Reich, Ronny; Baruch, Yuval (2016). "The Meaning of the Inscribed Stones at the Corners of the Herodian Temple Mount". Revue Biblique (1946–). 123 (1): 118–124. ISSN 0035-0907. JSTOR 44092415.

The Temple Mount has never been the focus of a modern archaeological excavation

- ^ Wendy Pullan; Maximilian Sternberg; Lefkos Kyriacou; Craig Larkin; Michael Dumper (2013). The Struggle for Jerusalem's Holy Places. Routledge. m/s. 9. ISBN 978-1-317-97556-4.

The sources for the first temple are solely biblical, and no substantial archaeological remains have been verified.

- ^ Yitzhak Reiter (2017-04-07). "Post-1967 Struggle over Al-Haram Al-Sharif/Temple Mount". Contested Holy Places in Israel–Palestine. London: Routledge. m/s. 20–50. doi:10.4324/9781315277271-3. ISBN 978-1-315-27727-1. Dicapai pada 2022-05-22.

- ^ Baker, Eric W.. The Eschatological Role of the Jerusalem Temple: An Examination of the Jewish Writings Dating from 586 BCE to 70 CE. Germany: Anchor Academic Publishing, 2015, pp. 361–362

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Avoda, Beit haBechira, 6:14.

- ^ Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, Bernard Avishai, 'Jews Don’t Have a ‘Holiest’ Site,' Haaretz 13 May :’The point is, this kind of recklessness not only offended secular democrats, it vulgarized what “holy” has meant for most observant Jews, too. Not coincidentally, more than 85 percent of Israel’s Haredi Jews oppose prayer on the Mount, for reasons having to do with purity and impurity that cannot be resolved in “our time.” Advocates of such prayer and sacrifice tend to be, like Goren, Orthodox-nationalist zealots educated in local yeshivas and identified with the neo-Zionist settlement project. They are, like Islamists, fanatics warped by violence and nationalist fantasy – “Jewists,” not Jews.‘

- ^ Sam Sokol, Should Jews Be Allowed to Pray on the Temple Mount? Many Israelis Think So, Poll Shows,' Haaretz 3 May 2022: '86.5 percent of ultra-Orthodox Jews opposed prayer for reasons of halakha, while national religious (51 percent), traditional religious (54.5 percent) and traditional non-religious respondents (49 percent) supported worship on the mount for nationalist reasons. Many rabbis, and almost all ultra-Orthodox ones, prohibit their followers from ascending the Temple Mount due to concerns over ritual purity.'

Pautan luar[sunting | sunting sumber]

- Templemount.org

- New Evidence of the Royal Stoa and Roman Flames. Biblical Archaeology Review

- Virtual Walking Tour of Al-Haram Al-Sharif ("The Noble Sanctuary")

- Temple Mount Sifting Project

Ralat petik: Tag <ref> untuk kumpulan "lower-alpha" ada tetapi tag <references group="lower-alpha"/> yang sepadan tidak disertakan