Masjid al-Aqsa

| Al-Aqsa Al-Haram al-Qudsi al-Syarif | |

|---|---|

| المسجد الأقصى الحرم القدسي الشريف | |

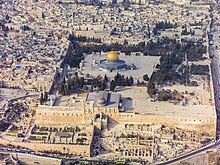

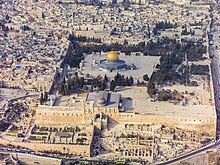

Pandangan atas kawasan masjid al-Aqsa | |

| Info asas | |

| Lokasi | Kota Lama Baitulmaqdis |

| Koordinat geografi | 31°46′41″N 35°14′10″E / 31.778°N 35.236°EKoordinat: 31°46′41″N 35°14′10″E / 31.778°N 35.236°E |

| Agama | Islam |

| Negara | |

| Pentadbiran | Jabatan Wakaf dan Hal Ehwal Masjid Al-Aqsa Baitulmaqdis |

| Pemimpin | Imam Muhammad Ahmad Hussein |

| Penerangan seni bina | |

| Jenis seni bina | Masjid |

| Gaya seni bina | Awal Islam, Mamluk |

| Arah muka bangunan | utara-barat laut |

| Spesifikasi | |

| Arah bahagian hadapan bangunan | utara-barat laut |

| Kapasiti | c. 400,000 (anggaran) |

| Bil. kubah | dua buah besar + puluhan kecil |

| Bil. menara masjid | empat |

| Tinggi menara masjid | 37 meter (121 ka) (tertinggi) |

| Bahan binaan | Batu kapur (dinding luar, menara, gerbang) stalaktit (menara), emas, plumbum dan batu (kubah), marmar putih (ruang dalam) dan mozek[1] |

| Sebahagian daripada siri berkaitan |

| Baitulmaqdis |

|---|

|

| Sebahagian daripada siri berkaitan |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Sebahagian daripada siri berkaitan |

| Al-Aqsa |

|---|

Masjid Shah Jahan, Woking, Baitulmuqaddis Timur Masjid Shah Jahan, Woking, Baitulmuqaddis Timur |

Al-Aqsa (Arab: الأقصى, rumi: Al-Aqṣā) atau Masjid al-Aqsa (Arab: المسجد الأقصى, rumi: al-Masjid al-Aqṣā)[2] ialah sebuah kawasan bangunan-bangunan keagamaan Islam yang terletak di atas Bukit Kuil, juga dikenali sebagai Al-Haram al-Syarif (Arab: الحرم القدسي الشريف, lit. 'Perkarangan mulia yang suci'), dalam Kota Lama Baitulmaqdis, yang turut merangkumi Kubah al-Sakhrah, banyak masjid dan ruang sembahyang, madrasah, zawiyah, khalwah dan struktur keagamaan dan kubah yang lain, juga empat menara mengelilinginya. Masjid jamek atau ruang solat utama kawasan ini ialah Masjid al-Aqsa, yang turut dikenali sebagai Masjid al-Qibli atau al-Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā. Sesetengah sumber menyebut ia dikenali sebagai Masjid al-Aqsa, manakala kawasan yang lebih luas kadang kala disebut sebagai kompleks Masjid al-Aqsa atau kawasan Masjid al-Aqsa bagi mengelakkan kekeliruan.[3]

Semasa pemerintahan khalifah al-Rasyid, Umar bin Al-Khatab (634-644M) atau khalifah Umaiyah, Muawiyah (661-680M), sebuah dewan solat kecil dalam kawasan ini didirikan berhampiran tapak masjid. Masjid pada waktu kini, terletak di dinding selatan kawasan ini, pada asalnya dibina oleh khalifah Umaiyah ke-5, Abdul Malik (685-705M) atau penggantinya al-Walid I (705-715M) (atau kedua-duanya) sebagai sebuah masjid jamek selari dengan Kubah al-Sakhrah, sebuah binaan peringatan Islam. Selepas musnah akibat gempa bumi pada 746, masjid ini dibina semula pada 758 oleh khalifah Abbasiyah, al-Mansur. Ia kemudiannya dibesarkan pada 780 oleh khalifah Abbasiyah, al-Mahdi, yang kemudiannya mempunyai lima belas buah ruang sayap dan kubah utama. Walau bagaimanapun, ia sekali lagi musnah semasa gempa bumi Lembah Jordan 1033. Masjid ini dibina semula pada khalifah Fatimiyah, al-Zahir (1021–1036), yang mengurangkan kepada tujuh ruang sayap aisles tetapi menghiasi bahagian dalamannya dengan gerbang tengah yang rumit dilitupi mozek tumbuh-tumbuhan; struktur binaan yang dikekalkan kini.

Semasa zaman pengubahsuaiannya, pemerintah Islam yang mentadbir telah membina bahagian tambahan masjid ini, seperti kubah, menara, muka bangunan, mimbar dan binaan dalaman. Semasa penaklukan Tentera Salib pada 1099, masjid ini digunakan sebagai istana; juga sebagai pejabat utama pentadbir agama Kesateria Templar. Selepas kawasan ini dikuasai semula oleh Islam melalui Salahuddin Al-Ayubi pada 1187, fungsi bangunan ini sebagai masjid dikembalikan. Lebih banyak projek pengubahsuaian, pembaikan dan perluasan dilakukan pada abad seterusnya di bawah pemerintahan kesultanan Ayubiyah, kesultanan Mamluk, kesultanan Usmaniyah, Majlis Tertinggi Islam Palestin Bermandat, dan semasa pendudukan Jordan ke atas Tebing Barat. Sejak permulaan penjajahan Israel ke atas Tebing Barat, masjid ini kekal diletakkan di bawah pentadbiran bebas oleh Jabatan Wakaf dan Hal Ehwal Masjid Al-Aqsa Baitulmaqdis, di bawah Kementerian Wakaf, Hal Ehwal Islam dan Tempat Suci Kerajaan Jordan.[4]

Al-Aqsa memegang kepentingan geopolitik yang tinggi disebabkan lokasinya di atas Bukit Kuil, berdekatan tempat suci dan bersejarah lain bagi Islam, Kristian dan Yahudi, dan menjadi titik ledakan utama konflik Israel–Palestin kini.[5]

Pentakrifan[sunting | sunting sumber]

Penggunaan istilah bahasa Melayu "Masjid al-Aqsa" ialah terjemahan bagi kedua-dua perkataan Arab al-Masjid al-Aqṣā (ٱلْمَسْجِد ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ) dan Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā (جَامِع ٱلْأَقْصَىٰ), yang mempunyai pengertian tersendiri dalam bahasa Arab.[6][7][8] Al-Masjid al-Aqṣā merujuk kepada Surah ke-17 (Al-Israk) dalam al-Quran – "masjid yang jauh" – secara tradisinya merujuk kepada keseluruhan Bukit Kuil, sementara Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā digunakan secara khusus bagi bangunan masjid jamik yang berkubah perak.[6][7][8] Penulis Arab dan Parsi seperti ahli geografi abad ke-10 al-Muqaddasi,[9] sarjana abad ke-11 Nasir Khusraw,[9] ahli geografi abad ke-12 al-Idrisi[10] dan ulama abad ke-15 Mujir al-Din,[11][12] begitu juga orientalis Amerika dan British abad ke-19 Edward Robinson,[6] Guy Le Strange dan Edward Henry Palmer menerangkan istilah Masjid al-Aqsa merujuk kepada keseluruhan dataran yang dikenali sebagai Bukit Kuil (Temple Mount) atau Kawasan Mulia (Haram al-Syarif) – termasuklah keseluruhan kawasan Kubah al-Sakhrah, pancuran, gerbang, dan empat menara – kerana tiada mana-mana bangunan ini wujud semasa al-Quran diturunkan.[7][13][14] Al-Muqaddasi merujuk kepada bangunan selatan sebagai Al Mughattâ ("kawasan dilitup") dan Nasir Khusraw merujuknya dalam perkataan Parsi sebagai Pushish (juga bermaksud "kawasan dilitup," sama seperti "Al Mughatta") atau Maqsurah (kawasan sebahagian).[9]

Semasa pemerintahan Mamluk[15] (1260–1517) dan Usmaniyah (1517–1917), kawasan yang lebih luas mula dikenali dengan Haram al-Syarif, atau al-Ḥaram ash-Sharīf (Arab: اَلْـحَـرَم الـشَّـرِيْـف), yang diterjemah sebagai "Kawasan Mulia". Ia mencerminkan istilah Masjid al-Haram di Mekah;[16][17][18][19] Istilah ini menaikkan taraf kawasan ini sebagai Haram, yang mana sebelum ini hanya diperuntukkan kepada Masjid al-Haram di Mekah dan Masjid Nabawi di Madinah.[20] Penggunaan nama Haram al-Syarif oleh warga Palestin tempatan berkurangan dalam dekad terkini, tetapi lebih menggunakan nama lama Masjid al-Aqsa.[20]

Sejarah[sunting | sunting sumber]

Keindahan dan kecantikan Masjid al-Aqsa di Baitulmaqdis menarik ribuan pelancong daripada pelbagai agama mengunjunginya setiap tahun. Kebanyakan orang bukan Islam percaya ia merupakan bekas tapak Kuil Sulaiman yang dimusnahkan oleh Nebuchadnezzar dari Babylon pada tahun 586 SM, atau tapak Kuil Kedua yang dimusnahkan oleh Empayar Rom pada tahun 70 masihi.

Bagi orang Muslim di seluruh dunia, kawasan ini mempunyai keistimewaannya yang tersendiri kerana ia adalah kawasan berlakunya Israk Mikraj yang mana Nabi Muhammad s.a.w. menerima perintah solat lima waktu sehari semalam dan juga sebagai kiblat pertama umat Islam.

Israk Mikraj[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada tahun kesembilan misi Rasulullah s.a.w., lebih kurang tahun 620 masihi, Nabi Muhammad berjaga pada waktu malam untuk melakukan ibadah di Masjidil Haram, Makkah. Selepas beribadat, baginda tertidur seketika dekat Kaabah. Malaikat Jibril datang mengejutkan Rasulullah daripada tidur dan membawa baginda ke hujung Masjidil Haram. Menanti mereka ialah sejenis makhluk yang bernama Al Buraq. Rasulullah kemudiannya menaiki Al Buraq yang kemudian membawa baginda ke Masjidil Aqsa di Baitulmaqdis dalam sekelip mata.

Apabila tiba di Baitulmaqdis, Rasulullah turun daripada Al Buraq dan bersembahyang dekat sebuah batu. Nabi Ibrahim a.s, Nabi Musa a.s, Nabi Isa a.s dan nabi-nabi yang lain berkumpul bersama dan bersolat bersama-sama baginda. Nabi Muhammad s.a.w. dipersembahkan semangkuk arak dan semangkuk susu. Rasulullah s.a.w. memilih susu. Malaikat Jibril a.s kemudiannya berkata "Ternyata engkau telah memilih ajaran yang sebenar". Rasulullah kemudiannya naik ke langit untuk menerima perintah menunaikan solat kepada umat Islam.

Penaklukan Baitulmaqdis[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada tahun 638 masihi, selepas beberapa tahun kewafatan Nabi Muhammad s.a.w., tentera Islam mengepung Baitulmaqdis. Ketua Gereja Baitulmaqdis, Sophronius, menyerahkan kota itu selepas kepungan yang singkat. Cuma terdapat satu syarat iaitu perbincangan mengenai penyerahan itu mestilah menerusi Khalifah Saidina Umar Al Khatab sendiri, khalifah kedua Islam.

Saidina Umar memasuki Baitulmaqdis dengan berjalan. Tidak ada pertumpahan darah dan tidak ada pembunuhan oleh tentera Islam. Sesiapa yang ingin meninggalkan Baitulmaqdis dengan segala harta benda mereka, dibenarkan berbuat demikian. Sesiapa yang ingin terus tinggal dijamin keselamatan nyawa, harta benda, dan tempat beribadat mereka. Semua ini terkandung dalam Perjanjian Umariyya.

Buat pertama kalinya Baitulmaqdis terselamat daripada bermandi darah. Mengikut cerita, Saidina Umar kemudiannya menemani Sophronious ke Gereja Makam Suci yang mana Saidina Umar ditawarkan bersolat di dalamnya. Saidina umar menolak takut akan timbulnya syak wasangka yang dapat menjejaskan penggunaan gereja itu sebagai tempat beribadat penganut Kristian. Saidina Umar sebaliknya menunaikan solat di sebelah selatan gereja tersebut yang kini merupakan tapak Masjid Umar di Baitulmaqdis.

Saidina Umar kemudiannya meminta supaya dibawa ke tempat Masjidil Aqsa dengan ditemani beratus-ratus orang Islam. Saidina Umar mendapati tempat itu dipenuhi dengan habuk dan sampah sarap. Saidina Umar terus mengarahkan supaya tempat itu dibersihkan dengan serta merta. Sebuah masjid yang diperbuat daripada kayu kemudiannya didirikan pada masa Saidina Umar di sebelah paling selatan Al Haram Al Sharif.

Bangunan dan seni bina[sunting | sunting sumber]

Kepentingan Masjdil Aqsa di dalam Islam dapat ditunjukkan melalui struktur-struktur lain yang mengelilingi Kubah Al-Sakhrah dan Masjid al-Aqsa.

Muzium Islam[sunting | sunting sumber]

Koleksi Al Quran yang lengkap dan seramik Islam. Di samping itu koleksi duit syiling dan tembikar bersama-sama senapang, pedang dan pisau di muzium tertua di Baitulmaqdis ini.

Pintu-pintu[sunting | sunting sumber]

- Bab al-Maghribah- Pintu ini menuju ke penempatan orang Maghribi. Kawasan ini dimusnahkan oleh Israel pada tahun 1967 dan penduduknya menjadi pelarian. Kawasan ini sekarang hanya boleh diakses oleh orang Yahudi yang mana sekarang mereka membina sebuah plaza.

- Bab al-Silsilah.

- Bab as-Salaam

- Bab al-Matarah

- Bab al-Qattanin

- Bab al-Hadid

- Bab al-Nazer- Pintu majlis. Pihak Awqaf yang menguruskan Al Haram Al Sharif mempunyai sebuah pejabat di luar pintu ini.

- Bab al-Atim

- Bab al-Hittah

- Bab al-Asbat

- Bab al-Zahabi- Imam al Ghazali dikatakan mengajar di perkarangan pintu ini. Masyarakat Kristian percaya bahawa Nabi Isa a.s. akan kembali ke dunia melalui pintu ini.

- Bab al-Rahman

- Bab at-Taubat

(*Nota: Bab ialah pintu atau pagar dalam Bahasa Arab.)

Musala al Marwani[sunting | sunting sumber]

Hanya di sebelah bawah di sebelah tenggara Al Haram Al Sharif terdapatnya sebuah kawasan yang disangka sebagai Solomon's Stables (kandang kuda Nabi Sulaiman a.s.). Ia sebenarnya ialah sebuah bangunan Umayyah pada kurun ke 8M.

Musala al-Qibli[sunting | sunting sumber]

Sebuah masjid kayu pada asalnya dibina di sini oleh Saidina Umar Al-Khatab, kahlifah kedua Islam pada tahun 638M. Selepas pembinaan Kubah Al-Sakhrah, Khalifah Abdul Malik ibni Marwan mengarahkan supaya dibina sebuah masjid bagi mengantikan masjid yang sedia ada. Anaknya Al Walid ibni Abdul Malik menyiapkan pembinaan masjid ini semasa pemerintahannya pada 705M. Masjid ini harus tidak dikelirukan dengan keseluruhan kawasan ini yang juga dikenali sebagai Masjid al-Aqsa Al Haram Al Sharif. Setiap inci kawasan ini amat suci dan tidak boleh dirundingkan.

Kubah al-Silsilah[sunting | sunting sumber]

Di sebelah timur Kubah Al-Sakhrah, Kubah al-Silsilah dibina oleh Abdul Malik ibni Marwan dan menandakan tengah Al Haram Al Sharif.

Kubah al-Nabawi[sunting | sunting sumber]

Kubah yang dibina untuk memuji Nabi Muhammad s.a.w.. Dibaiki pada tahun 1620 oleh Farruk Bey, Gabenor Baitulmaqdis.

Kubah al-Mikraj[sunting | sunting sumber]

Kubah Mikraj dibina untuk mengingati peristiwa Nabi Muhammad s.a.w. naik ke langit untuk menerima perintah solat.

Kubah al-Khalili[sunting | sunting sumber]

Sebuah bangunan kurun ke-18 khas untuk Sheikh Muhammad al Khalili.

Kubah al-Nahawiah[sunting | sunting sumber]

Dibina pada tahun 1207 masihi oleh Amir Hassan ad-Din sebagai sebuah sekolah kesusasteraan.

Mimbar Burhan ad-Din[sunting | sunting sumber]

Pada asalnya dibina pada kurun ke-7. Dinamakan sempena nama Qadi Baitulmaqdis.

Dalam budaya rakyat[sunting | sunting sumber]

Istilah "al-Aqsa" sebagai simbol atau jenama menjadi terkenal dan tersebar luas di kawasan Palestin.[21] Sebagai contoh, Intifadah al-Aqsa (sebuah kebangkitan yang berlaku pada September 2000), Briged Syuhada al-Aqsa (sebuah gabungan pertahanan orang Palestin di Tebing Barat), al-Aqsa TV (saluran televsiyen rasmi yang digerakkan Hamas), Universiti al-Aqsa (universiti Palestin yang ditubuhkan pada 1991 di Genting Gaza), Jund al-Aqsa (sebuah pertubuhan jihad Salafi yang giat semasa Perang Saudara Syria), makalah berkala ketenteraan Jordan yang diterbitkan sejak awal 1970-an, dan pertubuhan cawangan utara dan selatan Gerakan Islam di Israel semuanya dinamakan sebagai Al-Aqsa bersempena nama tempat ini.[21]

Slogan politik terkenal Al-Aqsa dalam bahaya digunakan untuk menentang usaha Pengabdi Bukit Kuil untuk mengawal kawasan ini, juga untuk menentang usaha penyiasatan arkeologi yang dianggap akan menjejaskan struktur asas kawasan atau cubaan untuk membuktikan kewujudan kuil yahudi purba di tempat tersebut.[22][23][24]

Galeri[sunting | sunting sumber]

Lihat juga[sunting | sunting sumber]

| Wikimedia Commons mempunyai media berkaitan Masjid al-Aqsa |

Pautan luar[sunting | sunting sumber]

- (Inggeris) Maklumat mengenai Al Haram Al Sharif

- ^ Al-Ratrout, H. A., The Architectural Development of Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Early Islamic Period, ALMI Press, London, 2004.

- ^ Williams, George (1849). The Holy City: Historical, Topographical and Antiquarian Notices of Jerusalem. Parker. m/s. 143–160. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 22 June 2022.

The following detailed account of the Haram es-Sherif, with some interesting notices of the City, is extracted from an Arabic work entitled " The Sublime Companion to the History of Jerusalem and Hebron, by Kadi Mejir-ed-din, Ebil-yemen Abd-er-Rahman, El-Alemi," who died A. H. 927, (A. d. 1521)… "I have at the commencement called attention to the fact that the place now called by the name Aksa (i. e. the most distant), is the Mosk [Jamia] properly so called, at the southern extremity of the area, where is the Minbar and the great Mihrab. But in fact Aksa is the name of the whole area enclosed within the walls, the dimensions of which I have just given, for the Mosk proper [Jamia], the Dome of the Rock, the Cloisters, and other buildings, are all of late construction, and Mesjid el-Aksa is the correct name of the whole area."

and also von Hammer-Purgstall, J.F. (1811). "Chapitre vingtième. Description de la mosquée Mesdjid-ol-aksa, telle qu'elle est de nos jours, (du temps de l'auteur, au dixième siècle de l'Hégire, au seizième après J. C.)". Fundgruben des Orients (dalam bahasa Perancis). 2. Gedruckt bey A. Schmid. m/s. 93. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 22 June 2022.Nous avons dès le commencement appelé l'attention sur que l'endroit, auquel les hommes donnent aujourd'hui le nom d'Aksa, c'est à-dire, la plus éloignée, est la mosquée proprement dite, bâtie à l'extrêmité méridionale de l'enceinte où se trouve la chaire et le grand autel. Mais en effet Aksa est le nom de l'enceinte entière, en tant qu'elle est enfermée de murs, dont nous venons de donner la longueur et la largeur, car la mosquée proprement dite, le dôme de la roche Sakhra, les portiques et les autres bâtimens, sont tous des constructions récentes, et Mesdjidol-aksa est le véritable nom de toute l'enceinte. (Le Mesdjid des arabes répond à l'ίερόν et le Djami au ναός des grecs.)

- ^ * Tucker, S.C.; Roberts, P. (2008). The Encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli Conflict: A Political, Social, and Military History [4 volumes]: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO history reference online. ABC-CLIO. m/s. 70. ISBN 978-1-85109-842-2. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 19 June 2022.

Al-Aqsa Mosque The al-Aqsa Mosque (literally, "farthest mosque") is both a building and a complex of religious buildings in Jerusalem. It is known to Muslims as al-Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary) and to Jews and Christians as the Har ha-Bayit or Temple Mount. The whole area of the Noble Sanctuary is considered by Muslims to be the al-Aqsa Mosque, and the entire precinct is inviolable according to Islamic law. It is considered specifically part of the waqf (endowment) land that had included the Western Wall (Wailing Wall), property of an Algerian family, and more generally a waqf of all of Islam. When viewed as a complex of buildings, the al-Aqsa Mosque is dominated and bounded by two major structures: the al-Aqsa Mosque building on the east and the Dome of the Rock (or the Mosque of Omar) on the west. The Dome of the Rock is the oldest holy building in Islam.

- "Jerusalem holy site clashes fuel fears of return to war". BBC News. 2022-04-22. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 24 May 2022. Dicapai pada 30 May 2022.

Whole site also considered by Muslims as Al Aqsa Mosque

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre (2022-04-04). "39 COM 7A.27 - Decision". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 30 May 2022. Dicapai pada 2022-05-29.

…the historic Gates and windows of the Qibli Mosque inside Al-Aqsa Mosque/ Al-Haram Al-Sharif, which is a Muslim holy site of worship and an integral part of a World Heritage Site

- The Survey of Western Palestine, Jerusalem, 1884, p.119: "The Jamia el Aksa, or 'distant mosque' (that is, distant from Mecca), is on the south, reaching to the outer wall. The whole enclosure of the Haram is called by Moslem writers Masjid el Aksa, 'praying-place of the Aksa,' from this mosque."

- Yitzhak Reiter: "This article deals with the employment of religious symbols for national identities and national narratives by using the sacred compound in Jerusalem (The Temple Mount/al-Aqsa) as a case study. The narrative of The Holy Land involves three concentric circles, each encompassing the other, with each side having its own names for each circle. These are: Palestine/Eretz Israel (i.e., the Land of Israel); Jerusalem/al-Quds and finally The Temple Mount/al-Aqsa compound...Within the struggle over public awareness of Jerusalem's importance, one particular site is at the eye of the storm—the Temple Mount and its Western Wall—the Jewish Kotel—or, in Muslim terminology, the al-Aqsa compound (alternatively: al-Haram al-Sharif) including the al-Buraq Wall... "Al-Aqsa" for the Palestinian-Arab-Muslim side is not merely a mosque mentioned in the Quran within the context of the Prophet Muhammad's miraculous Night Journey to al-Aqsa which, according to tradition, concluded with his ascension to heaven (and prayer with all of the prophets and the Jewish and Christian religious figures who preceded him); rather, it also constitutes a unique symbol of identity, one around which various political objectives may be formulated, plans of action drawn up and masses mobilized for their realization", "Narratives of Jerusalem and its Sacred Compound" Diarkibkan 21 Mei 2022 di Wayback Machine, Israel Studies 18(2):115-132 (July 2013)

- Annika Björkdahl and Susanne Buckley-Zistel: "The site is known in Arabic as Haram al-Sharif – the Noble Sanctuary – and colloquially as the Haram or the al-Aqsa compound; while in Hebrew, it is called Har HaBeit – the Temple Mount." Annika Björkdahl; Susanne Buckley-Zistel (1 May 2016). Spatialising Peace and Conflict: Mapping the Production of Places, Sites and Scales of Violence. Palgrave Macmillan UK. m/s. 243–. ISBN 978-1-137-55048-4. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 21 May 2022. Dicapai pada 21 May 2022.

- Mahdi Abdul Hadi:"Al-Aqsa Mosque, also referred to as Al-Haram Ash-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary), comprises the entire area within the compound walls (a total area of 144,000 m2) - including all the mosques, prayer rooms, buildings, platforms and open courtyards located above or under the grounds - and exceeds 200 historical monuments pertaining to various Islamic eras. According to Islamic creed and jurisprudence, all these buildings and courtyards enjoy the same degree of sacredness since they are built on Al-Aqsa's holy grounds. This sacredness is not exclusive to the physical structures allocated for prayer, like the Dome of the Rock or Al-Qibly Mosque (the mosque with the large silver dome)"Mahdi Abdul Hadi Diarkibkan 2020-02-16 di Wayback Machine Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs; Tim Marshall: "Many people believe that the mosque depicted is called the Al-Aqsa; however, a visit to one of Palestine's most eminent intellectuals, Mahdi F. Abdul Hadi, clarified the issue. Hadi is chairman of the Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs, based in East Jerusalem. His offices are a treasure trove of old photographs, documents, and symbols. He was kind enough to spend several hours with me. He spread out maps of Jerusalem's Old City on a huge desk and homed in on the Al-Aqsa compound, which sits above the Western Wall. "The mosque in the Al-Aqsa [Brigades] flag is the Dome of the Rock. Everyone takes it for granted that it is the Al-Aqsa mosque, but no, the whole compound is Al-Aqsa, and on it are two mosques, the Qibla mosque and the Dome of the Rock, and on the flags of both Al-Aqsa Brigades and the Qassam Brigades, it is the Dome of the Rock shown," he said. Tim Marshall (4 July 2017). A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols. Simon and Schuster. m/s. 151–. ISBN 978-1-5011-6833-8. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 12 September 2019. Dicapai pada 17 April 2018.*Hughes, Aaron W. (2014). Theorizing Islam: Disciplinary Deconstruction and Reconstruction. Religion in Culture. Taylor & Francis. m/s. 45. ISBN 978-1-317-54594-1. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 24 June 2022.

Although later commentators would debate whether or not this journey was a physical one or took place at an internal level, it would come to play a crucial role in establishing Muhammad's prophetic credentials. In the first part of this journey, referred to as the isra, he traveled from the Kaba in Mecca to "the farthest mosque" (al-masjid al-aqsa), identified with the Temple Mount in Jerusalem: the al-Aqsa mosque that stands there today eventually took its name from this larger precinct, in which it was constructed.

*Sway, Mustafa A. (2015), "Al-Aqsa Mosque: Do Not Intrude!", Palestine - Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture, 20/21 (4): 108–113, ProQuest 1724483297, diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023, dicapai pada 28 July 2022 – melalui ProQuest,Ahmed ibn Hanbal (780–855): "Verily, 'Al-Aqsa' is a name for the whole mosque which is surrounded by the wall, the length and width of which are mentioned here, for the building that exists in the southern part of the Mosque, and the other ones such as the Dome of the Rock and the corridors and other [buildings] are novel (muhdatha)." Mustafa Sway: More than 500 years ago, when Mujir Al-Din Al-Hanbali offered the above definition of Al-Aqsa Mosque in the year 900 AH/1495, there were no conflicts, no occupation and no contesting narratives surrounding the site.

*Omar, Abdallah Marouf (2017). "Al-Aqsa Mosque's Incident in July 2017: Affirming the Policy of Deterrence". Insight Turkey. 19 (3): 69–82. doi:10.25253/99.2017193.05. JSTOR 26300531.In a treaty signed by Jordan and the Palestinian Authority on March 31, 2013, both sides define al-Aqsa Mosque as being "al-Masjid al-Aqsa with its 144 dunums, which include the Qibli Mosque of al-Aqsa, the Mosque of the Dome of the Rock, and all its mosques, buildings, walls, courtyards". ... Israel insists on identifying al-Aqsa Mosque as being a small building. ... Nonetheless, the Executive Board of UNESCO adopted the Jordanian definition of al-Aqsa Mosque in its Resolution (199 EX/PX/DR.19.1 Rev).

*"Occupied Palestine: draft decision (199 EX/PX/DR.19.1 REV), UNESCO Executive Board". UNESCO. 2016. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000244378.

- "Jerusalem holy site clashes fuel fears of return to war". BBC News. 2022-04-22. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 24 May 2022. Dicapai pada 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Arab states neglect Al-Aqsa says head of Jerusalem Waqf". Al-Monitor. 5 September 2014. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 24 April 2016. Dicapai pada 5 April 2016.

- ^ The Archaeology of the Holy Land: From the Destruction of Solomon's Temple to the Muslim Conquest Diarkibkan 15 Julai 2020 di Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press, Jodi Magness, page 355

- ^ a b c Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine. John Murray.

The Jámi'a el-Aksa is the mosk alone; the Mesjid el-Aksa is the mosk with all the sacred enclosure and precincts, including the Sükhrah. Thus the words Mesjid and Jāmi'a differ in usage somewhat like the Greek ίερόν and ναός.

- ^ a b c Palmer, E. H. (1871). "History of the Haram Es Sherif: Compiled from the Arabic Historians". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 3 (3): 122–132. doi:10.1179/peq.1871.012. ISSN 0031-0328.

EXCURSUS ON THE NAME MASJID EL AKSA. In order to understand the native accounts of the sacred area at Jerusalem, it is essentially necessary to keep in mind the proper application of the various names by which it is spoken of. When the Masjid el Aksa is mentioned, that name is usually supposed to refer to the well-known mosque on the south side of the Haram, but such is not really the case. The latter building is called El Jámʻi el Aksa, or simply El Aksa, and the substructures are called El Aksa el Kadímeh (the ancient Aksa), while the title El Masjid el Aksa is applied to the whole sanctuary. The word Jámi is exactly equivalent in sense to the Greek συναγωγή, and is applied to the church or building in which the worshippers congregate. Masjid, on the other hand, is a much more general term; it is derived from the verb sejada "to adore," and is applied to any spot, the sacred character of which would especially incite the visitor to an act of devotion. Our word mosque is a corruption of masjid, but it is usually misapplied, as the building is never so designated, although the whole area on which it stands may be so spoken of. The Cubbet es Sakhrah, El Aksa, Jam'i el Magharibeh, &c., are each called a Jami, but the entire Haram is a masjid. This will explain how it is that 'Omar, after visiting the churches of the Anastasis, Sion, &c., was taken to the "Masjid" of Jerusalem, and will account for the statement of Ibn el 'Asa'kir and others, that the Masjid el Aksa measured over 600 cubits in length-that is, the length of the whole Haram area. The name Masjid el Aksa is borrowed from the passage in the Coran (xvii. 1), when allusion is made to the pretended ascent of Mohammed into heaven from ·the temple of Jerusalem; "Praise be unto Him who transported His servant by night from El Masjid el Haram (i.e., 'the Sacred place of Adoration' at Mecca) to El Masjid el Aksa (i.e., 'the Remote place of Adoration' at Jerusalem), the precincts of which we have blessed," &c. The title El Aksa, "the Remote," according to the Mohammedan doctors, is applied to the temple of Jerusalem "either because of its distance from Mecca, or because it is in the centre of the earth."

- ^ a b Warren, Charles; Conder, Claude Reignier (1884). The survey of Western Palestine. Jerusalem. Published for the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. London. m/s. 119 – melalui Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Translated from the Works of the Medieval Arab Geographers. Houghton, Mifflin. m/s. 96. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 31 July 2022.

Great confusion is introduced into the Arab descriptions of the Noble Sanctuary by the indiscriminate use of the terms Al Masjid or Al Masjid al Akså, Jami' or Jami al Aksâ; and nothing but an intimate acquaintance with the locality described will prevent a translator, ever and again, misunderstanding the text he has before him-since the native authorities use the technical terms in an extraordinarily inexact manner, often confounding the whole, and its part, under the single denomination of "Masjid." Further, the usage of various writers differs considerably on these points : Mukaddasi invariably speaks of the whole Haram Area as Al Masjid, or as Al Masjid al Aksî, "the Akså Mosque," or "the mosque," while the Main-building of the mosque, at the south end of the Haram Area, which we generally term the Aksa, he refers to as Al Mughattâ, "the Covered-part." Thus he writes "the mosque is entered by thirteen gates," meaning the gates of the Haram Area. So also "on the right of the court," means along the west wall of the Haram Area; "on the left side" means the east wall; and "at the back" denotes the northern boundary wall of the Haram Area. Nasir-i-Khusrau, who wrote in Persian, uses for the Main-building of the Aksâ Mosque the Persian word Pushish, that is, "Covered part," which exactly translates the Arabic Al Mughatta. On some occasions, however, the Akså Mosque (as we call it) is spoken of by Näsir as the Maksurah, a term used especially to denote the railed-off oratory of the Sultan, facing the Mihrâb, and hence in an extended sense applied to the building which includes the same. The great Court of the Haram Area, Nâsir always speaks of as the Masjid, or the Masjid al Akså, or again as the Friday Mosque (Masjid-i-Jum'ah).

- ^ Idrīsī, Muhammad; Jaubert, Pierre Amédée (1836). Géographie d'Édrisi (dalam bahasa Perancis). à l'Imprimerie royale. m/s. 343–344. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 31 July 2022.

Sous la domination musulmane il fut agrandi, et c'est (aujourd'hui) la grande mosquée connue par les Musulmans sous le nom de Mesdjid el-Acsa مسجد الأقصى. Il n'en existe pas au monde qui l'égale en grandeur, si l'on en excepte toutefois la grande mosquée de Cordoue en Andalousie; car, d'après ce qu'on rapporte, le toit de cette mosquée est plus grand que celui de la Mesdjid el-Acsa. Au surplus, l'aire de cette dernière forme un parallelogramme dont la hauteur est de deux cents brasses (ba'a), et le base de cents quatre-vingts. La moitié de cet espace, celle qui est voisin du Mihrab, est couverte d'un toit (ou plutôt d'un dôme) en pierres soutenu par plusieurs rangs de colonnes; l'autre est à ciel ouvert. Au centre de l'édifice est un grand dôme connu sous le nom de Dôme de la roche; il fut orné d'arabesques en or et d'autres beaux ouvrages, par les soins de divers califes musulmans. Le dôme est percé de quatre portes; en face de celle qui est à l'occident, on voit l'autel sur lequel les enfants d'Israël offraient leurs sacrifices; auprès de la porte orientale est l'église nommée le saint des saints, d'une construction élégante; au midi est une chapelle qui était à l'usage des Musulmans; mais les chrétiens s'en sont emparés de vive force et elle est restée en leur pouvoir jusqu'à l'époque de la composition du présent ouvrage. Ils ont converti cette chapelle en un couvent où résident des religieux de l'ordre des templiers, c'est-à-dire des serviteurs de la maison de Dieu.

Also at Williams, G.; Willis, R. (1849). "Account of Jerusalem during the Frank Occupation, extracted from the Universal Geography of Edrisi. Climate III. sect. 5. Translated by P. Amédée Jaubert. Tome 1. pp. 341—345.". The Holy City: Historical, Topographical, and Antiquarian Notices of Jerusalem. J.W. Parker. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 31 July 2022. - ^ Ralat petik: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; teks bagi rujukanMujiralDin2tidak disediakan - ^ Mustafa Abu Sway (Fall 2000). "The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Islamic Sources". Journal of the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR): 60–68. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 29 May 2022. Dicapai pada 29 May 2022.

Quoting Mujir al-Din: "Verily, ‘Al-Aqsa’ is a name for the whole mosque which is surrounded by the wall, the length and width of which are mentioned here, for the building that exists in the southern part of the Mosque, and the other ones such as the Dome of the Rock and the corridors and other [buildings] are novel"

- ^ Le Strange, Guy (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Translated from the Works of the Medieval Arab Geographers. Houghton, Mifflin. Diarkibkan daripada yang asal pada 19 July 2023. Dicapai pada 29 May 2022.

THE AKSÀ MOSQUE. The great mosque of Jerusalem, Al Masjid al Aksà, the "Further Mosque," derives its name from the traditional Night Journey of Muhammad, to which allusion is made in the words of the Kuran (xvii. I)... the term "Mosque" being here taken to denote the whole area of the Noble Sanctuary, and not the Main-building of the Aksà only, which, in the Prophet's days, did not exist.

- ^ Strange, Guy le (1887). "Description of the Noble Sanctuary at Jerusalem in 1470 A.D., by Kamâl (or Shams) ad Dîn as Suyûtî". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 19 (2): 247–305. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00019420. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25208864. S2CID 163050043.

…the term Masjid (whence, through the Spanish Mezquita, our word Mosque) denotes the whole of the sacred edifice, comprising the main building and the court, with its lateral arcades and minor chapels. The earliest specimen of the Arab mosque consisted of an open courtyard, within which, round its four walls, run colonades or cloisters to give shelter to the worshippers. On the side of the court towards the Kiblah (in the direction of Mekka), and facing which the worshipper must stand, the colonade, instead of being single, is, for the convenience of the increased numbers of the congregation, widened out to form the Jami' or place of assembly… coming now to the Noble Sanctuary at Jerusalem, we must remember that the term 'Masjid’ belongs not only to the Aksa mosque (more properly the Jami’ or place of assembly for prayer), but to the whole enclosure with the Dome of the Rock in the middle, and all the other minor domes and chapels.

- ^ St Laurent, B., & Awwad, I. (2013). The Marwani Musalla in Jerusalem: New Findings. Jerusalem Quarterly.

- ^ Jarrar, Sabri (1998). "Suq al-Ma'rifa: An Ayyubid Hanbalite Shrine in Haram al-Sharif". Dalam Necipoğlu, Gülru (penyunting). Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World (ed. Illustrated, annotated). Brill. m/s. 85. ISBN 978-90-04-11084-7.

"Al-Masjid al-Aqsa" was the standard designation for the whole sanctuary until the Ottoman period, when it was superseded by "al-Haram al-Sharif”; "al-Jami’ al-Aqsa" specifically referred to the Aqsa Mosque, the mughatta or the covered aisles, the site on which ‘Umar founded the first mosque amidst ancient ruins.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (2000). "The Haram al-Sharif: An Essay in Interpretation" (PDF). Bulletin of the Royal Institute for Inter-Faith Studies. Constructing the Study of Islamic Art. 2 (2). Diarkibkan daripada yang asal (PDF) pada 2016-04-14.

It is only at a relatively late date that the Muslim holy space in Jerusalem came to be referred to as al-haram al-sharif (literally, the Noble Sacred Precinct or Restricted Enclosure, often translated as the Noble Sanctuary and usually simply referred to as the Haram). While the exact early history of this term is unclear, we know that it only became common in Ottoman times, when administrative order was established over all matters pertaining to the organization of the Muslim faith and the supervision of the holy places, for which the Ottomans took financial and architectural responsibility. Before the Ottomans, the space was usually called al-masjid al-aqsa (the Farthest Mosque), a term now reserved to the covered congregational space on the Haram, or masjid bayt al-maqdis (Mosque of the Holy City) or, even, like Mecca's sanctuary, al-masjid al-ḥarâm.

- ^ Schick, Robert (2009). "Geographical Terminology in Mujir al-Din's History of Jerusalem". Dalam Khalid El-Awaisi (penyunting). Geographical Dimensions of Islamic Jerusalem. Cambridge Scholars Publisher. m/s. 91–106. ISBN 978-1-4438-0834-7.

Mujir al-Din defined al-Masjid al-Aqsā as the entire compound, acknowledging that in common usage it referred to the roofed building at the south end of the compound. As he put it (1999 v.2, 45; 1973 v.2, 11), the jami' that is in the core of al-Masjid al-Aqsa at the qiblah where the Friday service takes place is known among the people as "al-Masjid al-Aqsa", and (1999 v.2, 63-64; 1973 v.2, 24) what is known among the people as "al-Aqsa" is the jami in the core of the masjid in the direction of the giblah, where the minbar and the large mihrab are. The truth of the matter is that the term "al-Aqsa" is for all of the masjid and what the enclosure walls surround. What is intended by "al-Masjid al-Aqsā" is everything that the enclosure walls surround. Mujir al-Din did not identify al-Masjid al-Aqsā by the alternative term "al-Haram al-Sharif". That term began to be used in the Mamluk period and came into more general use in the Ottoman period. He only used the term when giving the official title of the government-appointed inspector of the two noble harams of Jerusalem and Hebron (Nazir al-Haramavn al-Sharifayn). While Mujir al-Din did not explicitly discuss why the masjid of Bayt al-Magdis "is not called the haram" (1999 v.1, 70; 1973 v.1, 7), he may well have adopted the same position as Ibn Taymiyah, his fellow Hanbali in the early 14th century (Ziyarat Bayt al-Maqdis Matthews 1936, 13; Iqtida' al-Sirat al-Mustaqim Mukhalafat Ashab al-Jahim Memon 1976: 316) in rejecting the idea that al-Masjid al-Aqsa (or the tomb of Abraham in Hebron) can legitimately be called a haram, because there are only three harams (where God prohibited hunting): Makkah, Madinah, and perhaps Täif. However Mujir al-Din was not fully consistent and also used al-Masiid al-Aqsã to refer to the roofed building, as for example when he referred to al-Nasir Muhammad installing marble in al-Masjid al-Aqsà (1999 v.2, 161; 1973 v.2, 92); he used the term al-Jami al-Aqsa in the parallel passage (1999 v.2, 396; 1973 v.2, 271)

- ^ Wazeri, Yehia Hassan (2014-02-20). "The Farthest Mosque or the Alleged Temple an Analytic Study". Journal of Islamic Architecture. Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University. 2 (3). doi:10.18860/jia.v2i3.2462. ISSN 2356-4644. S2CID 190588084.

Many people think that Al-Masjid al-Aqsa is only the mosque established south of the Dome of the Rock, where the obligatory five daily prayers are performed now. Actually, Al-Masjid al-Aqsa is a term that applies to all parts of the Masjid, including the area encompassed within the wall, such as the gates, the spacious yards, the mosque itself, the Dome of the Rock, Al-Musalla Al-Marawani, the corridors, domes, terraces, free drinking water (springs), and other landmarks, like minarets on the walls. Furthermore, the whole mosque is unroofed with the exception of the building of the Dome of the Rock and Al-Musalla Al-Jami`, which is known by the public as Al-Masjid al-Aqsa. The remaining area, however, is a yard of the mosque. This is agreed upon by scholars and historians, and accordingly, the doubled reward for performing prayer therein is attained if the prayer is performed in any part of the area encompassed by the wall. Indeed, Al-Masjid al-Aqsa, which is mentioned in Almighty Allah's Glorious Book in the first verse of Sura Al-Isra' is the blessed place that is now called the Noble Sanctuary (Al-Haram Al-Qudsi Ash-Sharif) which is enclosed within the great fence and what is built over it. Moreover, what applies to the mosque applies by corollary to the wall encircling it, since it is part of it. Such is the legal definition of Al-Masjid al-Aqsa. Regarding the concept (definition) of Al-Masjid al-Aqsa, Shaykh `Abdul-Hamid Al-Sa'ih, former Minister of (Religious) Endowments and Islamic Sanctuaries in Jordan said: "The term Al-Masjid al-Aqsa, for the Muslim public, denotes all that is encircled by the wall of Al-Masjid al-Aqsa, including the gates". Therefore, (the legally defined) Al-Masjid al-Aqsa and Al-Haram Al-Qudsi Ash-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary) are two names for the same place, knowing that Al-Haram Ash-Sharif is a name that has only been coined recently.

- ^ a b Ralat petik: Tag

<ref>tidak sah; teks bagi rujukanReiter2tidak disediakan - ^ a b Reiter, Yitzhak (2008). Jerusalem and Its Role in Islamic Solidarity. Palgrave Macmillan US. m/s. 21–23. ISBN 978-0-230-61271-6.

During the Middle Ages, when the issue of Jerusalem's status was a point of controversy, the supporters of Jerusalem's importance (apparently after its liberation from Crusader control) succeeded in attributing to al-Quds or to Bayt-al-Maqdis (the Arabic names for Jerusalem) the status of haram that had been accorded to the sacred compound. The site was thus called al-Haram al-Sharif, or al-Haram al-Qudsi al-Sharif. Haram, from an Arabic root meaning "prohibition," is a place characterized by a particularly high level of sanctity – a protected place in which blood may not be shed, trees may not be felled, and animals may not be hunted. The status of haram was given in the past to the Sacred Mosque in Mecca and to the Mosque of the Prophet in al-Madina (and some also accorded this status to the Valley of Wajj in Ta'if on the Arabian Peninsula?). Thus, al-Masjid al-Aqsa became al-Haram al-Sharif (the Noble Sanctuary) in order to emphasize its exalted status alongside the two other Muslim sanctuaries. Although, as noted before, Ibn-Taymiyya refuted the haram status of the Jerusalem mosque, al-Aqsa's upgrading to haram status was successful and has prevailed. It became a commonly accepted idea and one referred to in international forums and documents. It was, therefore, surprising that during the 1980s the Palestinians gradually abandoned the name that had been given to the Haram/Temple Mount compound in apparent honor of Jerusalem's status as third in sanctity – al-Haram al-Sharif – in favor of its more traditional name-al-Aqsa. An examination of relevant religious texts clarifies the situation: since the name al-Aqsa appears in the Quran, all Muslims around the world should be familiar with it; thus it is easier to market the al-Aqsa brand-name. An additional factor leading to a return to the Qur'anic name is an Israeli demand to establish a Jewish prayer space inside the open court of the compound. The increased use of the name al-Aqsa is particularly striking against the background of what is written on the Web site of the Jerusalem Waqf, under the leadership of (former) Palestinian mufti Sheikh Ikrima Sabri. There it is asserted that "al Masjid al-Aqsa was erroneously called by the name al-Haram al-Qudsi al-Sharif," and that the site's correct name is al-Aqsa. This statement was written in the context of a fatwa in response to a question addressed to the Web site's scholars regarding the correct interpretation of the Isra' verse in the Quran (17:1), which tells of the Prophet Muhammad's miraculous Night Journey from the "Sacred Mosque to the Farthest Mosque" – al-Aqsa. In proof of this, Sabri quotes Ibn-Taymiyya, who denied the existence of haram in Jerusalem, a claim that actually serves those seeking to undermine the city's sacred status. Sabri also states that Arab historians such as Mujir al-Din al-Hanbali, author of the famed fifteenth-century work on Jerusalem, do not make use of the term "haram" in connection with the al-Aqsa site. Both Ibn-Taymiyya and Mujir al-Din were affiliated with the Hanbali School of law-the relatively more puritan stream in Islam that prevailed in Saudi Arabia. The Hanbalies rejected innovations, such as the idea of a third haram. One cannot exclude the possibility that the Saudis, who during the 1980s and 1990s donated significant funds to Islamic institutions in Jerusalem, exerted pressure on Palestinian-Muslim figures to abandon the term "haram" in favor of "al-Aqsa". The "al-Aqsa" brand-name has thus become popular and prevalent. Al-Haram al-Sharif is still used by official bodies (the Organization of the Islamic Conference [OIC], the Arab League), in contrast to religious entities. The public currently uses the two names interchangeably. During the last generation, increasing use has been made of the term "al-Aqsa" as a symbol and as the name of various institutions and organizations. Thus, for example, the Jordanian military periodical that has been published since the early 1970s is called al-Aqsa; the Palestinian police unit established by the PA in Jericho is called the Al-Aqsa Division; the Fatah's armed organization is called the Al-Aqsa Brigades; the Palestinian Police camp in Jericho is called the Al-Aqsa Camp; the Web sites of the southern and northern branches of the Islamic movement in Israel and the associations that they have established are called al-Aqsa; the Intifada that broke out in September 2000 is called the al-Aqsa Intifada and the Arab summit that was held in the wake of the Intifada's outbreak was called the al-Aqsa Summit. These are only a few examples of a growing phenomenon.

- ^ Larkin, Craig; Dumper, Michael (2012). "In Defense of Al-Aqsa: The Islamic Movement inside Israel and the Battle for Jerusalem". Middle East Journal. Middle East Institute. 66 (1): 31–52. doi:10.3751/66.1.12. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 41342768. S2CID 144916717. Dicapai pada 2023-08-01.

- ^ Reiter, Y. (2008). Jerusalem and Its Role in Islamic Solidarity. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-0-230-61271-6. Dicapai pada 2023-08-01.

- ^ Center, Berkley; Affairs, World (2021-05-08). ""Al-Aqsa Is in Danger": How Jerusalem Connects Palestinian Citizens of Israel to the Palestinian Cause". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs. Dicapai pada 2023-08-01.